Journal

Announcing David Aaron’s TEFAF Maastricht 2026 presentation

David Aaron has been exhibiting at TEFAF Maastricht since 2022 and will once again present a suite of significant pieces of antiquity with exceptional provenance and condition spanning Roman, Greek, Egyptian, and Near Eastern cultures.

Stele of Medeia

Stele of Medeia

Highlights will include a remarkable rare Greek stele dated circa 375-350 B.C. - one of very few surviving examples dedicated to a Parthenos, a young Athenian woman of marriageable age who has not yet wed.

What makes this work extraordinary is its rarity. The term Parthenoi refers to the brief transitional period between childhood and entry into adulthood through marriage making depictions on Greek stele scarce and the number of known Parthenoi steles make up a very small percentage of academia studying the subject matter.

Torso of a Youth

Limestone Baboon

Finally, David Aaron will present an Egyptian Limestone Baboon from 664-343 B.C., 26th-30th Dynasty, Late Period. Baboons were highly regarded in ancient Egypt as an embodiment of Thoth, god of the moon and also as an adviser to Ra the sun god. This particular piece is dedicated to the role of the baboon in the rising and setting of the sun, we know this because the baboon’s arms are positioned outstretched in solar worship.

For further updates on our TEFAF Maastricht presentation sign up to our enew via the ‘Join Mailing List’ link at the bottom of our website.

Published 05/02/2026

From 14 – 19 March David Aaron will exhibit at TEFAF Maastricht art fair located at stand 804 in MECC Maastricht conference center. TEFAF Maastricht is widely regarded as the world’s premier fair for fine art, antiques, and design, and brings together 7,000 years of art history at the one fair.

David Aaron has been exhibiting at TEFAF Maastricht since 2022 and will once again present a suite of significant pieces of antiquity with exceptional provenance and condition spanning Roman, Greek, Egyptian, and Near Eastern cultures.

Stele of Medeia

Stele of MedeiaHighlights will include a remarkable rare Greek stele dated circa 375-350 B.C. - one of very few surviving examples dedicated to a Parthenos, a young Athenian woman of marriageable age who has not yet wed.

What makes this work extraordinary is its rarity. The term Parthenoi refers to the brief transitional period between childhood and entry into adulthood through marriage making depictions on Greek stele scarce and the number of known Parthenoi steles make up a very small percentage of academia studying the subject matter.

Torso of a Youth

Further highlights include a Roman Torso of a Youth from the 1st-2nd century A.D. from the collection of Italian art dealer Stefano Bardini. Research by David Aaron uncovered new provenance for the Torso of a Youth dating back to 1898, through historic images in gallerist Stefano Bardini’s innovative photographic archive.

Limestone Baboon

Finally, David Aaron will present an Egyptian Limestone Baboon from 664-343 B.C., 26th-30th Dynasty, Late Period. Baboons were highly regarded in ancient Egypt as an embodiment of Thoth, god of the moon and also as an adviser to Ra the sun god. This particular piece is dedicated to the role of the baboon in the rising and setting of the sun, we know this because the baboon’s arms are positioned outstretched in solar worship.

For further updates on our TEFAF Maastricht presentation sign up to our enew via the ‘Join Mailing List’ link at the bottom of our website.

Westminster Lord Mayor Locum Tenens unveils Paul Vanstone’s 'Carrara Triceratops Skull' sculpture

Published 02/02/2026

On Thursday 22 January David Aaron hosted the official unveiling of Paul Vanstone’s striking Carrara Triceratops Skull sculpture with the Westminster City Council’s Lord Mayor Locum Tenens, Honorary Alderman Frances Blois formally opening the new public artwork to much fanfare.

The new installation is a unique collaboration between Mayfair art gallery David Aaron and acclaimed figurative sculptor Paul Vanstone who took inspiration from a 68-million-year-old Triceratops skull exhibited by the gallery at Frieze Masters 2025 in Regent’s Park. Carving the piece over 60 days from a 10-tonne block of marble, the artist has reinterpreted a prehistoric icon through modern craftsmanship for Mayfair locals and visitors to enjoy for the next two years.

The Triceratops sculpture marks the second occasion that David Aaron has presented a sculpture inspired by a dinosaur in Berkeley Square – in 2023 a bronze juvenile Tyrannosaurus Rex sculpture, affectionately known as the Berkeley Square T Rex, was displayed in the Square. The bronze took inspiration from a fossil called Chomper which David Aaron presented at Frieze Masters that same year.

Official unveiling

David Aaron hosted special guest Paul Vanstone, representatives from the Westminster City Council, collaborators involved in the making of the sculpture and valued supporters of the artist and gallery for the celebration.

Guests in attendance were treated to an in conversation with Vanstone, hosted by one of David Aaron’s Directors Jonathan Aaron, where the audience heard about the artist’s process in selecting the white Carrara marble on a trip to Italy, the challenges of carving a sculpture at such a grand scale and his inspiration for the artwork.

Paul Vanstone speaks at the unveiling of Vanstone’s 'Carrara Triceratops Skull' sculpture with Mayfair art gallery David Aaron. Photo: Gabrielle Thomas

Westminster City Council Lord Mayor Locum Tenens, Honorary Alderman Frances Blois; Jonathan Aaron, Director, David Aaron; and Councillor Patrick Lilley at the unveiling of Vanstone’s 'Carrara Triceratops Skull' sculpture with Mayfair art gallery David Aaron. Photo: Gabrielle Thomas

Paul Vanstone and guests at the unveiling of Vanstone’s 'Carrara Triceratops Skull' sculpture with Mayfair art gallery David Aaron. Photo: Gabrielle Thomas

The new installation is a unique collaboration between Mayfair art gallery David Aaron and acclaimed figurative sculptor Paul Vanstone who took inspiration from a 68-million-year-old Triceratops skull exhibited by the gallery at Frieze Masters 2025 in Regent’s Park. Carving the piece over 60 days from a 10-tonne block of marble, the artist has reinterpreted a prehistoric icon through modern craftsmanship for Mayfair locals and visitors to enjoy for the next two years.

The Triceratops sculpture marks the second occasion that David Aaron has presented a sculpture inspired by a dinosaur in Berkeley Square – in 2023 a bronze juvenile Tyrannosaurus Rex sculpture, affectionately known as the Berkeley Square T Rex, was displayed in the Square. The bronze took inspiration from a fossil called Chomper which David Aaron presented at Frieze Masters that same year.

Paul Vanstone, Lord Mayor Locum Tenens, Honorary Alderman Frances Blois, and Jonathan Aaron at the unveiling of Vanstone’s 'Carrara Triceratops Skull' sculpture with Mayfair art gallery David Aaron. Photo: Gabrielle Thomas

Official unveiling

David Aaron hosted special guest Paul Vanstone, representatives from the Westminster City Council, collaborators involved in the making of the sculpture and valued supporters of the artist and gallery for the celebration.

Guests in attendance were treated to an in conversation with Vanstone, hosted by one of David Aaron’s Directors Jonathan Aaron, where the audience heard about the artist’s process in selecting the white Carrara marble on a trip to Italy, the challenges of carving a sculpture at such a grand scale and his inspiration for the artwork.

Paul Vanstone speaks at the unveiling of Vanstone’s 'Carrara Triceratops Skull' sculpture with Mayfair art gallery David Aaron. Photo: Gabrielle Thomas

Council support plays a pivotal role

The display of the sculpture was made possible through the generous support of the Westminster City Council’s Berkeley Square Public Art program which included the allocation of the space and installation of a new electrical system allowing for a state of the art lighting system to illuminate the sculpture throughout the evening, creating a decidedly different viewing experience to seeing the white marble in the daylight.

David Aaron was delighted to host the Council’s Lord Mayor Locum Tenens, Honorary Alderman Frances Blois and Councillor Patrick Lilley who spoke at the event about the importance of access to public art for the local community and visitors to the area.

The display of the sculpture was made possible through the generous support of the Westminster City Council’s Berkeley Square Public Art program which included the allocation of the space and installation of a new electrical system allowing for a state of the art lighting system to illuminate the sculpture throughout the evening, creating a decidedly different viewing experience to seeing the white marble in the daylight.

David Aaron was delighted to host the Council’s Lord Mayor Locum Tenens, Honorary Alderman Frances Blois and Councillor Patrick Lilley who spoke at the event about the importance of access to public art for the local community and visitors to the area.

Westminster City Council Lord Mayor Locum Tenens, Honorary Alderman Frances Blois; Jonathan Aaron, Director, David Aaron; and Councillor Patrick Lilley at the unveiling of Vanstone’s 'Carrara Triceratops Skull' sculpture with Mayfair art gallery David Aaron. Photo: Gabrielle Thomas

Insight into the artist’s process

Especially for the event Vanstone displayed two smaller studies of the Triceratops skull carved in a ghostly alabaster, demonstrating the process of developing the form of the Triceratops’ iconic horns.

Throughout the evening images and videos of the artist’s creative process were displayed for guests to gained a greater understanding of how Vanstone made the sculpture.

Paul Vanstone’s Carrara Triceratops Skull is now on display in Berkeley Square, Mayfair.

Especially for the event Vanstone displayed two smaller studies of the Triceratops skull carved in a ghostly alabaster, demonstrating the process of developing the form of the Triceratops’ iconic horns.

Throughout the evening images and videos of the artist’s creative process were displayed for guests to gained a greater understanding of how Vanstone made the sculpture.

Paul Vanstone’s Carrara Triceratops Skull is now on display in Berkeley Square, Mayfair.

Paul Vanstone and guests at the unveiling of Vanstone’s 'Carrara Triceratops Skull' sculpture with Mayfair art gallery David Aaron. Photo: Gabrielle Thomas

Guests at the unveiling of Vanstone’s 'Carrara Triceratops Skull' sculpture with Mayfair art gallery David Aaron. Photo: Gabrielle Thomas

Magic in Mayfair: Paul Vanstone's Carrara Triceratops Skull

Published 19/12/2025

Read time: 3min

In December 2025 prehistoric magic returns to Berkeley Square with a world first, life-size marble Triceratops skull sculpture carved by acclaimed British sculptor Paul Vanstone in collaboration with David Aaron.

Titled Carrara Triceratops Skull, 2025, Vanstone took inspiration from a 68-million-year-old sub-adult Triceratops from the Late Cretaceous Period, exhibited by David Aaron at Frieze Masters 2025. The public artwork was unveiled on 16 December as part of Westminster City Council’s Berkeley Square Public Art Programme.

Gleaming during the day and illuminated at night, visitors to Mayfair will have the opportunity to experience the Carrara Triceratops Skull for the next two years.

David Aaron is honoured to present this unique collaboration with Vanstone and introduce new audiences to not only his exceptional craftsmanship but also the joy of this iconic Triceratops form.

Paul Vanstone the artist

Following his studies at Central Saint Martins and the Royal College of Art, Vanstone went on to work in renowned marble carving studios near the Carrara quarries of Italy, as well as in Berlin and Rajasthan, before spending five years working as an assistant to leading British sculptor Anish Kapoor.

It was in Kapoor’s studio that Vanstone first worked in large scale sculpture with one of his first assignments being a 30-tonne sculpture. These years of hands-on experience and dedication to his craft prepared Vanstone for this singular commission.

Vanstone’s practice is material led working in stone from onyx, alabaster and marble sourced primarily from Italy, Portugal, and India. The material leads the direction of the work - the colour, the veining – and from there Vanstone develops the subject.

This commission signals a departure from Vanstone’s usual human subject inspiration and presented an opportunity and challenge to explore more natural forms through his practice.

Vanstone works out of a workshop in West London where he has established a not-for-profit community space which accommodates studio spaces for 50 artists.

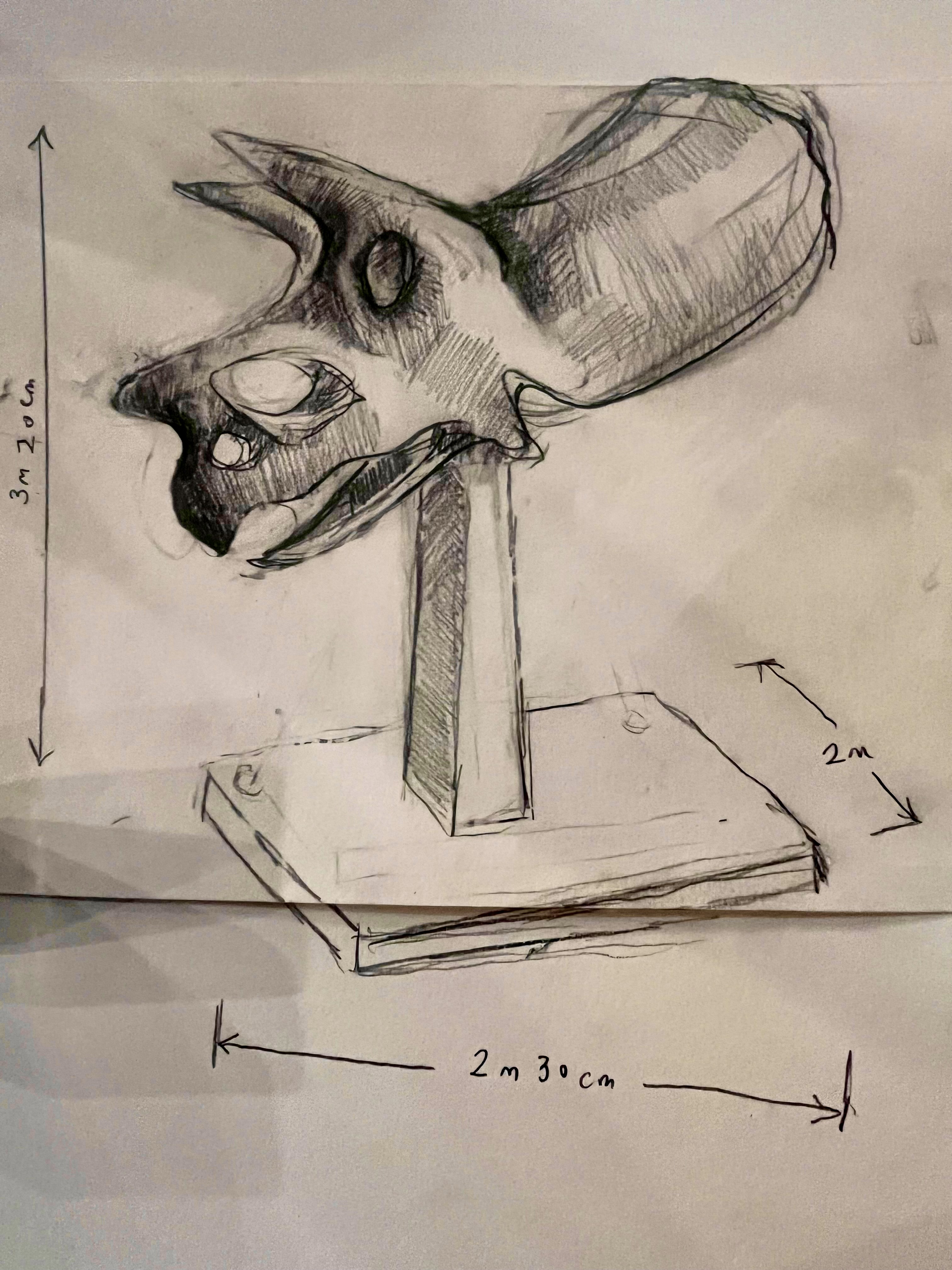

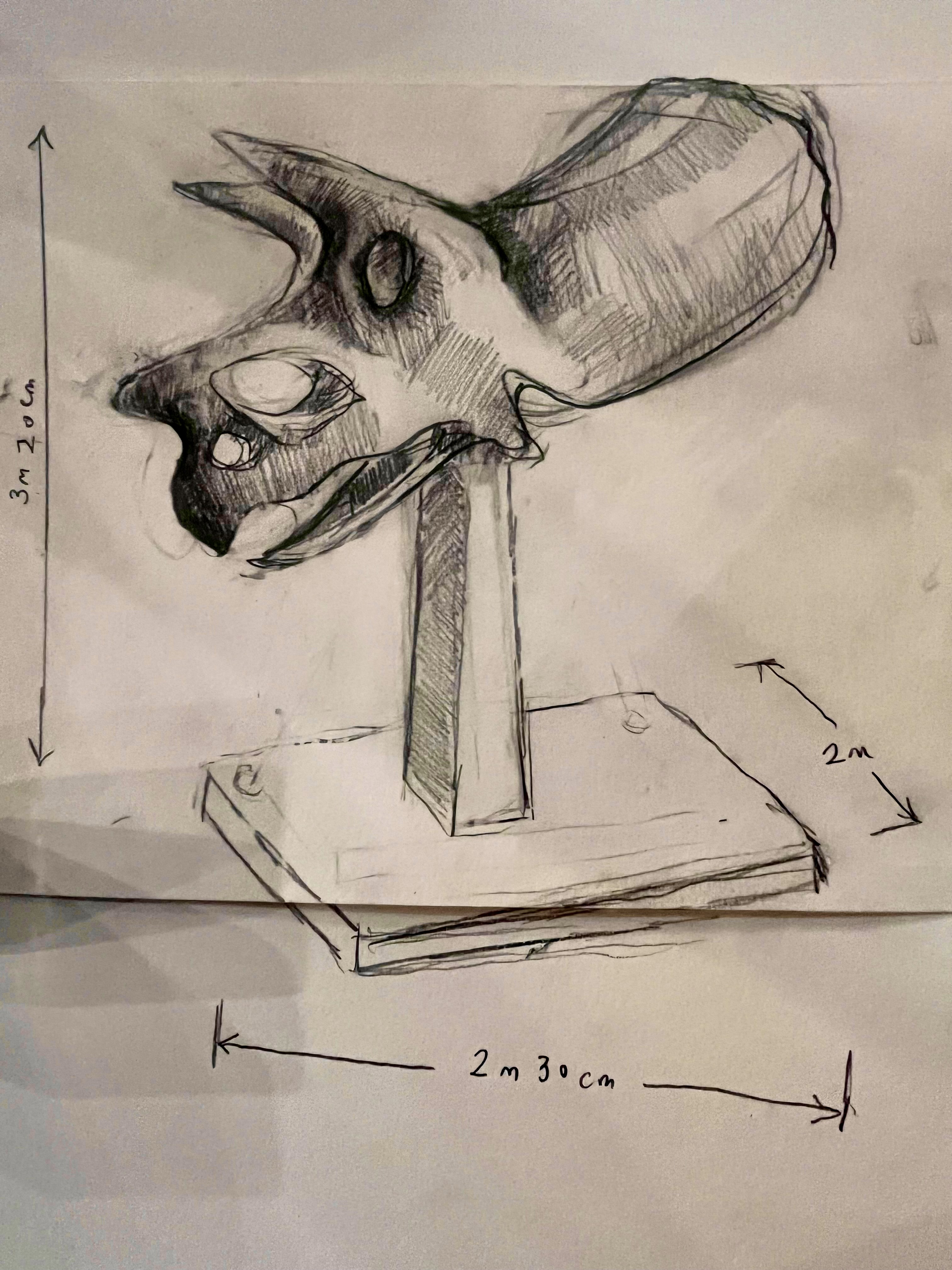

Making Carrara Triceratops Skull

The starting point for the making of Carrara Triceratops Skull was the real Triceratops skull fossil on display at David Aaron in Mayfair. Vanstone visited the fossil multiple times and sited experiencing the power and presence of the 68-million-year-old specimen as integral to informing his work. The volume and scale of the fossil as well as the iconic features such as the horns, the beak and the striking eyes left an impression with the artist.

During his visits Vanstone took photographs and sketches to inform the design of the sculpture and uniquely uses watercolours in his practice to make preparatory illustrations drafting the flow of the sculpture’s form.

From here Vanstone travelled to Carrara in Italy to visit marble stock yards and source the perfect stone for the project. While Vanstone often works in marble with strong veining, he decided that something different was needed for this project.

Vanstone selected a beautiful 10-tonne block of white Carrara marble with a very subtle veining that had a chalky, bonelike quality. Vanstone likened the white marble to a blank canvas from which he could carve the dinosaur into.

Over 60 days the artist carved the sculpture in his West London workshop alongside his colleague Liam Winship. To start they began hollowing out the frill at the back of the sculpture and then moved onto the beak and other defining features of the skull. The nearly haunting essence of the fossil’s eyes were particularly alluring for Vanstone and the lines radiating from the eyes are translated in the carving of the sculpture.

To finalise the sculpture was a lengthy polishing process which took around three weeks of hand polishing to complete the finish.

Magic in Mayfair

This unique artistic collaboration is the second public artwork presented by David Aaron in Mayfair, the first being a bronze sculpture inspired by a rare juvenile Tyrannosaurus Rex called ‘Chomper’ which was created in collaboration with a German foundry.

Dinosaurs continue to hold a unique position in the public imagination, embodying both awe and nostalgia. This collaboration between David Aaron and Paul Vanstone brings the monumental presence of a Triceratops into the heart of London, offering a bold reimagining of prehistoric form through modern craftsmanship.

Paul Vanstone’s Carrara Triceratops Skull will remain on display for the next two years.

Find out more about Paul Vanstone’s practice here: https://www.paulvanstone.co.uk/

Titled Carrara Triceratops Skull, 2025, Vanstone took inspiration from a 68-million-year-old sub-adult Triceratops from the Late Cretaceous Period, exhibited by David Aaron at Frieze Masters 2025. The public artwork was unveiled on 16 December as part of Westminster City Council’s Berkeley Square Public Art Programme.

Gleaming during the day and illuminated at night, visitors to Mayfair will have the opportunity to experience the Carrara Triceratops Skull for the next two years.

David Aaron is honoured to present this unique collaboration with Vanstone and introduce new audiences to not only his exceptional craftsmanship but also the joy of this iconic Triceratops form.

Paul Vanstone the artist

Following his studies at Central Saint Martins and the Royal College of Art, Vanstone went on to work in renowned marble carving studios near the Carrara quarries of Italy, as well as in Berlin and Rajasthan, before spending five years working as an assistant to leading British sculptor Anish Kapoor.

It was in Kapoor’s studio that Vanstone first worked in large scale sculpture with one of his first assignments being a 30-tonne sculpture. These years of hands-on experience and dedication to his craft prepared Vanstone for this singular commission.

Vanstone’s practice is material led working in stone from onyx, alabaster and marble sourced primarily from Italy, Portugal, and India. The material leads the direction of the work - the colour, the veining – and from there Vanstone develops the subject.

This commission signals a departure from Vanstone’s usual human subject inspiration and presented an opportunity and challenge to explore more natural forms through his practice.

Vanstone works out of a workshop in West London where he has established a not-for-profit community space which accommodates studio spaces for 50 artists.

Making Carrara Triceratops Skull

The starting point for the making of Carrara Triceratops Skull was the real Triceratops skull fossil on display at David Aaron in Mayfair. Vanstone visited the fossil multiple times and sited experiencing the power and presence of the 68-million-year-old specimen as integral to informing his work. The volume and scale of the fossil as well as the iconic features such as the horns, the beak and the striking eyes left an impression with the artist.

During his visits Vanstone took photographs and sketches to inform the design of the sculpture and uniquely uses watercolours in his practice to make preparatory illustrations drafting the flow of the sculpture’s form.

From here Vanstone travelled to Carrara in Italy to visit marble stock yards and source the perfect stone for the project. While Vanstone often works in marble with strong veining, he decided that something different was needed for this project.

Vanstone selected a beautiful 10-tonne block of white Carrara marble with a very subtle veining that had a chalky, bonelike quality. Vanstone likened the white marble to a blank canvas from which he could carve the dinosaur into.

Over 60 days the artist carved the sculpture in his West London workshop alongside his colleague Liam Winship. To start they began hollowing out the frill at the back of the sculpture and then moved onto the beak and other defining features of the skull. The nearly haunting essence of the fossil’s eyes were particularly alluring for Vanstone and the lines radiating from the eyes are translated in the carving of the sculpture.

To finalise the sculpture was a lengthy polishing process which took around three weeks of hand polishing to complete the finish.

Magic in Mayfair

This unique artistic collaboration is the second public artwork presented by David Aaron in Mayfair, the first being a bronze sculpture inspired by a rare juvenile Tyrannosaurus Rex called ‘Chomper’ which was created in collaboration with a German foundry.

Dinosaurs continue to hold a unique position in the public imagination, embodying both awe and nostalgia. This collaboration between David Aaron and Paul Vanstone brings the monumental presence of a Triceratops into the heart of London, offering a bold reimagining of prehistoric form through modern craftsmanship.

Paul Vanstone’s Carrara Triceratops Skull will remain on display for the next two years.

Find out more about Paul Vanstone’s practice here: https://www.paulvanstone.co.uk/

FRIEZE Masters: 2025

The Goddess by a Greywacke Master, an important Egyptian bust dating from the Reign of Pharaoh Amasis, circa 570 – 526 B.C

Our exhibition highlight was The Goddess by the Greywacke Master, an exquisite example of Egyptian sculpture attributed to an anonymous artist, the Greywacke Master, and dated to the reign of Amasis (c. 570-526 B.C.). The piece captivated visitors with its presence, fine detail and intriguing provenance from misattribution to rediscovery.

Published 21/10/2025

Read time: 2min

Last week marked our fifth year exhibiting at Frieze Masters. Here at David Aaron, we were delighted to return to Regent’s Park for one of the most anticipated events in the London art calendar.

Our stand, designed by Crawford and Grey, presented a carefully curated selection of works of ancient art and natural history. Greeting visitors at the entrance to the stand was a sub-adult Triceratops skull, which drew significant attention from collectors, curators, and the press alike. The specimen, offered at £650,000, sold on the Fair’s opening night, underscoring the continued global demand for rare and scientifically important fossils.

The Goddess by a Greywacke Master, an important Egyptian bust dating from the Reign of Pharaoh Amasis, circa 570 – 526 B.C

Our exhibition highlight was The Goddess by the Greywacke Master, an exquisite example of Egyptian sculpture attributed to an anonymous artist, the Greywacke Master, and dated to the reign of Amasis (c. 570-526 B.C.). The piece captivated visitors with its presence, fine detail and intriguing provenance from misattribution to rediscovery.

The fair also saw extensive media interest in our presentation. Our stand was featured in international outlets including Observer, ArtNews, Elle Decor Italia, FAD Magazine, and The Art Newspaper. Throughout the week, the stand was consistently busy, with visitors captivated by the stories behind each piece and the fascinating provenance of our works.

“Frieze Masters is always a pleasure to be part of. It is an exciting fair that draws an interesting, and, interested crowd of collectors, curators and art enthusiasts.” Salomon Aaron, Director

We would like to thank Emanuela Tarizzo, Director of Frieze Masters, as well as everyone at FRIEZE, Stabilo and all the contractors who worked tirelessly to bring our stand to life. We look forward to returning next year to continue sharing our passion for exceptional works from the ancient and natural worlds.

“Frieze Masters is always a pleasure to be part of. It is an exciting fair that draws an interesting, and, interested crowd of collectors, curators and art enthusiasts.” Salomon Aaron, Director

We would like to thank Emanuela Tarizzo, Director of Frieze Masters, as well as everyone at FRIEZE, Stabilo and all the contractors who worked tirelessly to bring our stand to life. We look forward to returning next year to continue sharing our passion for exceptional works from the ancient and natural worlds.

The Forgotten Princess

In 2025, the coffin is once again on public display, this time as part of the Making Egypt exhibition at the Young V&A, where visitors can view this exceptional object in person. Its presence not only brings ancient history into focus, but also underlines the value of sustained research, conservation, and responsible curation in the rediscovery of lost narratives.

The Forgotton Princess on display at Frieze Masters, 2024. Photo credit David Owens / co The Art Newspaper

The Forgotten Princess: Early Egyptologists

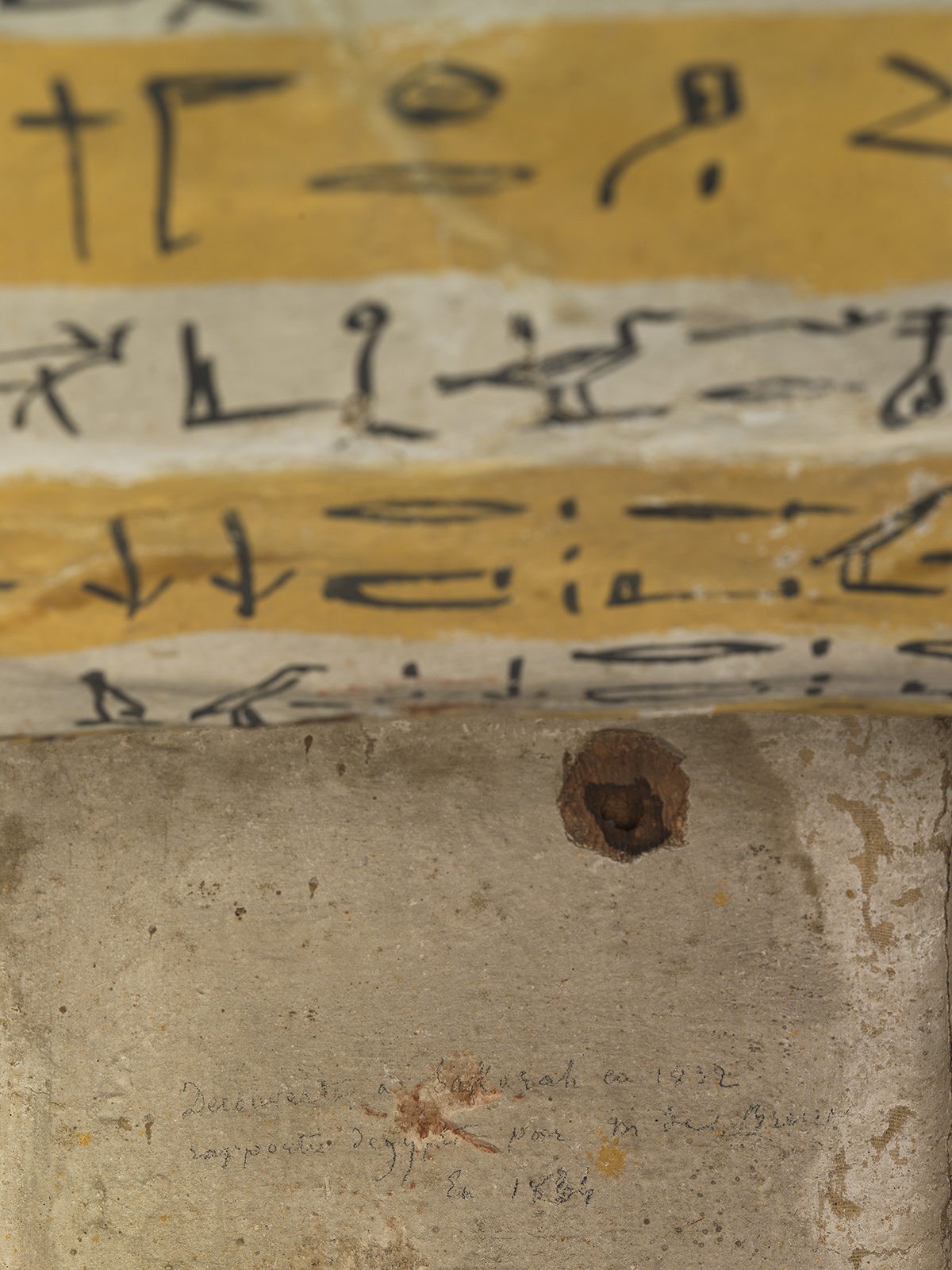

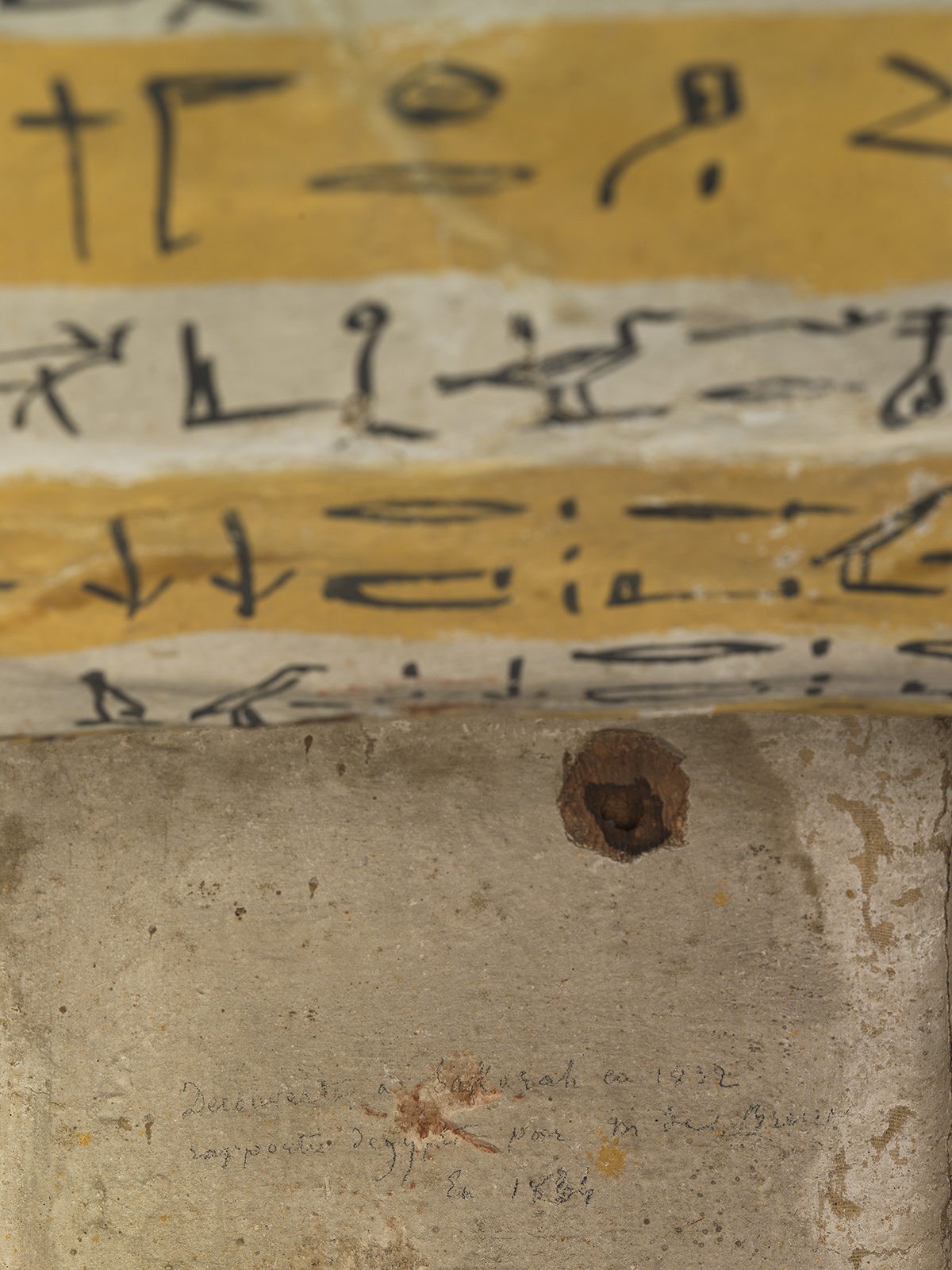

In 2014, a handwritten note was found on the inner base of the coffin, dating back to the early nineteenth-century:

‘Decouverte à Sakara en 1832 / rapportée d’egypte par M J de Breuv[ery] / En 1834’ (‘Discovered in Saqqara in 1832, removed from Egypt by M. J de Breuvery in 1834’)

The handwritten note can be seen on the inside of the base of the coffin.

The ‘M J Breuv[ery]’ in the note is Monsieur Jules Xavier Saguez de Breuvery (1805-1876), a French archaeologist who travelled the Near East, Egypt and Sudan with Édouard Pierre Marie de Cadalvène, between 1829 and 1832. De Breuvery and de Cadalvène published an account of their journey in four volumes, including their social and political commentary on the Ottoman Empire.

In 1829, de Breuvery and de Cadalvène began their journey through Egypt at Alexandria. They spent some time in the city, visiting sites such as Pompey’s Pillar and Cleopatra’s Needles. From here, they set out to Rosetta and Fuwwah, before continuing on to Damietta, where they began their journey down the Nile. Whilst staying in Cairo, the pair toured the pyramids of Giza, Heliopolis, and other notable regions from antiquity. They continued on to Faiyum and to the famous tombs at Beni Hasan, then down towards Abydos, Qurna, where they travelled to the temple at Denderra, before arriving at Thebes:

"Before us lay the immense plain which the ancient metropolis of Egypt covered with its countless buildings. Here and there rose on both banks of the Nile these gigantic ruins before which our republican phalanxes clapped their hands or presented arms, by a spontaneous movement, as if these ruins communicated an involuntary enthusiasm, as if they had a language intelligible to all." (translated) J. de Breuvery and Ed. de Cadalvène, L’Égypte et La Nubie (Paris, 1841), pp. 310-11

They explored much of the region around Thebes, visiting the temple at Karnak, the Ramesseum, the Valley of Kings, Medinet Habu, El-Assassif, and the city of Luxor. They sailed down the Nile past the temples of Esna, Edfu, and Kom Ombo, and through Aswan and Elephantine into what is now Sudan. Their tour then passed through Khartoum, Gebel Adda, Wadi Halfa, and Dongola, to Kordofan. From Kordofan they returned northwards, back to Saqqara. De Breuvery and de Cadalvène’s comprehensive itinerary reveals their keen interest in Egypt and its ancient history, and they even took care to describe the condition of the antiquities they saw on their route.

De Breuvery made several purchases of antiquities during their journey, several of which were inscribed with similar handwritten notes recording the dates he acquired them. Among the objects he brought back to his home at Saint-Germain-en-Laye in France are a caryatide statue from Halicarnassus (Musée du Louvre, Paris, MNC 1382) and the coffin of Princess Sopdet-em-haawt.

De Breuvery and de Cadalvène met many contemporary Egyptologists, archaeologists, and other travellers during their travels. For instance, they met famous explorer and early Egyptologist Robert Hay (1799-1863) at Beni Hasan.

"Mr. Hay, a wealthy English traveller and enthusiastic admirer of Egyptian architecture, was at Beny-Hassan when we arrived, busy carefully drawing the hieroglyphic paintings which decorate the speos of the mountain." (translated) De Breuvery and de Cadalvène, L’Égypte et La Nubie, p. 431.

Hay transcribed the paintings on the Speos Artemidos into one of his meticulous notebooks, where he also recorded a portion of the inscriptions on the coffin of Princess Sopdet-em-haawt. Hay recorded the coffin between 1829 and 1834, when he was living in the village of Gournah in the Theban area. Hay’s drawings, paintings, plans, notebooks and diaries are now in the collection of the British Library, including this notebook (Add.MSS.29827, fol. 83 verso).

Modern Rediscovery

In December 2013, the coffin was sold at Sotheby’s, New York. At this time, the coffin had remained closed, and the details of the internal hieroglyphics and the pencil note remained undiscovered. Still, the coffin had already sparked the interest of several scholars.

In 2009, when the coffin’s whereabouts were not public knowledge and using only the transcribed inscription in Hay’s notebook, Raphaële Meffre traced the lineage of Princess Sopdet-em-haawt in her article ‘Une Princesse Héracléopolitaine de l’Époque Libyenne: Sopdet(em)haaout’ (Revue d’Égyptologie, 60 (2009), pp. 215-221). As a descendant of two Libyan kings, the princess’s coffin can be dated to either the very end of the 25th Dynasty or, more likely, the beginning of the 26th. Sopdet-em-haawt was married to a member of one of the most important Theban families; her husband was involved in the cults of Amun and of Montu, whose priests were among the most influential people in Thebes from the end of the Libyan Period to the 26th Dynasty.

However, it was not until 2014 when the coffin was painstakingly cleaned, conserved, and opened by conservators that much of the internal hieroglyphs became visible, and the incredibly well-preserved striped interior inscriptions were uncovered. The new discoveries prompted Meffre to study the coffin in greater detail. In 2015, she published a complete, 54-page translation of the coffin’s internal and external inscriptions (‘Le cercueil intérieur de la princesse Sopdet-em-hââout et la famille des rois Roudamon et Peftjaouâuybastet’, Monuments et mémoires de la Fondation Eugène Piot, 94 (2015), pp. 7-59).

The Princess Sopdet-em-haawt lived during a pivotal regime shift between the end of the Third Intermediate Period and the establishment of the Late Period. Her coffin is highly important in expanding our knowledge of workshops in the Theban area at the beginning of the Late Period. This, alongside the extremely well-preserved decoration, given new life through extensive conservation, and the rediscovered nineteenth-century provenance, makes the coffin of Sopdet-em-haawt a truly unique example of an ancient Egyptian coffin on the market today.

Making Egypt - Exhibition at Young V&A

The coffin of Princess Sopdet-em-haawt is on view as part of Making Egypt, the major new exhibition at the Young V&A, running until 2 November 2025. The exhibition offers a rare chance to examine the coffin's beautifully preserved decoration up close, including the striking internal yellow and white stripes, and reflects on how ancient Egypt has influenced art, design and popular culture today.

The inner sarcophagus of Princess Sopdet-em-haawt on view as part of Making Egypt, Young V&A, 2025. Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Photo: David Parry

Published 18/07/2025

Read time: 4min

In 2014, the inner coffin of Princess Sopdet‑em‑haawt was opened for the first time in nearly two centuries. Inside, conservators discovered extensive heiroglyphics painted on wonderfully preserved bright-yellow and white stripes, as well as a handwritten note from the early 1830s.

As we begin preparations for Frieze Masters 2025, we wanted to take a moment to reflect on one of the stand-out pieces from our stand last year, a rediscovered royal coffin that attracted widespread public and media interest.

Exhibited under the title 'The Forgotten Princess', the coffin was the centrepiece for our Frieze Masters 2024 display. Its presence drew significant attention, not only for its beauty and intricate detailing, but because it is the only known royal Egyptian sarcophagus to have appeared on the art market.

As we begin preparations for Frieze Masters 2025, we wanted to take a moment to reflect on one of the stand-out pieces from our stand last year, a rediscovered royal coffin that attracted widespread public and media interest.

Exhibited under the title 'The Forgotten Princess', the coffin was the centrepiece for our Frieze Masters 2024 display. Its presence drew significant attention, not only for its beauty and intricate detailing, but because it is the only known royal Egyptian sarcophagus to have appeared on the art market.

In 2025, the coffin is once again on public display, this time as part of the Making Egypt exhibition at the Young V&A, where visitors can view this exceptional object in person. Its presence not only brings ancient history into focus, but also underlines the value of sustained research, conservation, and responsible curation in the rediscovery of lost narratives.

The Forgotton Princess on display at Frieze Masters, 2024. Photo credit David Owens / co The Art Newspaper

The Forgotten Princess: Early Egyptologists

In 2014, a handwritten note was found on the inner base of the coffin, dating back to the early nineteenth-century:

‘Decouverte à Sakara en 1832 / rapportée d’egypte par M J de Breuv[ery] / En 1834’ (‘Discovered in Saqqara in 1832, removed from Egypt by M. J de Breuvery in 1834’)

The handwritten note can be seen on the inside of the base of the coffin.

The ‘M J Breuv[ery]’ in the note is Monsieur Jules Xavier Saguez de Breuvery (1805-1876), a French archaeologist who travelled the Near East, Egypt and Sudan with Édouard Pierre Marie de Cadalvène, between 1829 and 1832. De Breuvery and de Cadalvène published an account of their journey in four volumes, including their social and political commentary on the Ottoman Empire.

In 1829, de Breuvery and de Cadalvène began their journey through Egypt at Alexandria. They spent some time in the city, visiting sites such as Pompey’s Pillar and Cleopatra’s Needles. From here, they set out to Rosetta and Fuwwah, before continuing on to Damietta, where they began their journey down the Nile. Whilst staying in Cairo, the pair toured the pyramids of Giza, Heliopolis, and other notable regions from antiquity. They continued on to Faiyum and to the famous tombs at Beni Hasan, then down towards Abydos, Qurna, where they travelled to the temple at Denderra, before arriving at Thebes:

"Before us lay the immense plain which the ancient metropolis of Egypt covered with its countless buildings. Here and there rose on both banks of the Nile these gigantic ruins before which our republican phalanxes clapped their hands or presented arms, by a spontaneous movement, as if these ruins communicated an involuntary enthusiasm, as if they had a language intelligible to all." (translated) J. de Breuvery and Ed. de Cadalvène, L’Égypte et La Nubie (Paris, 1841), pp. 310-11

They explored much of the region around Thebes, visiting the temple at Karnak, the Ramesseum, the Valley of Kings, Medinet Habu, El-Assassif, and the city of Luxor. They sailed down the Nile past the temples of Esna, Edfu, and Kom Ombo, and through Aswan and Elephantine into what is now Sudan. Their tour then passed through Khartoum, Gebel Adda, Wadi Halfa, and Dongola, to Kordofan. From Kordofan they returned northwards, back to Saqqara. De Breuvery and de Cadalvène’s comprehensive itinerary reveals their keen interest in Egypt and its ancient history, and they even took care to describe the condition of the antiquities they saw on their route.

De Breuvery made several purchases of antiquities during their journey, several of which were inscribed with similar handwritten notes recording the dates he acquired them. Among the objects he brought back to his home at Saint-Germain-en-Laye in France are a caryatide statue from Halicarnassus (Musée du Louvre, Paris, MNC 1382) and the coffin of Princess Sopdet-em-haawt.

De Breuvery and de Cadalvène met many contemporary Egyptologists, archaeologists, and other travellers during their travels. For instance, they met famous explorer and early Egyptologist Robert Hay (1799-1863) at Beni Hasan.

"Mr. Hay, a wealthy English traveller and enthusiastic admirer of Egyptian architecture, was at Beny-Hassan when we arrived, busy carefully drawing the hieroglyphic paintings which decorate the speos of the mountain." (translated) De Breuvery and de Cadalvène, L’Égypte et La Nubie, p. 431.

Hay transcribed the paintings on the Speos Artemidos into one of his meticulous notebooks, where he also recorded a portion of the inscriptions on the coffin of Princess Sopdet-em-haawt. Hay recorded the coffin between 1829 and 1834, when he was living in the village of Gournah in the Theban area. Hay’s drawings, paintings, plans, notebooks and diaries are now in the collection of the British Library, including this notebook (Add.MSS.29827, fol. 83 verso).

Modern Rediscovery

In December 2013, the coffin was sold at Sotheby’s, New York. At this time, the coffin had remained closed, and the details of the internal hieroglyphics and the pencil note remained undiscovered. Still, the coffin had already sparked the interest of several scholars.

In 2009, when the coffin’s whereabouts were not public knowledge and using only the transcribed inscription in Hay’s notebook, Raphaële Meffre traced the lineage of Princess Sopdet-em-haawt in her article ‘Une Princesse Héracléopolitaine de l’Époque Libyenne: Sopdet(em)haaout’ (Revue d’Égyptologie, 60 (2009), pp. 215-221). As a descendant of two Libyan kings, the princess’s coffin can be dated to either the very end of the 25th Dynasty or, more likely, the beginning of the 26th. Sopdet-em-haawt was married to a member of one of the most important Theban families; her husband was involved in the cults of Amun and of Montu, whose priests were among the most influential people in Thebes from the end of the Libyan Period to the 26th Dynasty.

However, it was not until 2014 when the coffin was painstakingly cleaned, conserved, and opened by conservators that much of the internal hieroglyphs became visible, and the incredibly well-preserved striped interior inscriptions were uncovered. The new discoveries prompted Meffre to study the coffin in greater detail. In 2015, she published a complete, 54-page translation of the coffin’s internal and external inscriptions (‘Le cercueil intérieur de la princesse Sopdet-em-hââout et la famille des rois Roudamon et Peftjaouâuybastet’, Monuments et mémoires de la Fondation Eugène Piot, 94 (2015), pp. 7-59).

The Princess Sopdet-em-haawt lived during a pivotal regime shift between the end of the Third Intermediate Period and the establishment of the Late Period. Her coffin is highly important in expanding our knowledge of workshops in the Theban area at the beginning of the Late Period. This, alongside the extremely well-preserved decoration, given new life through extensive conservation, and the rediscovered nineteenth-century provenance, makes the coffin of Sopdet-em-haawt a truly unique example of an ancient Egyptian coffin on the market today.

Making Egypt - Exhibition at Young V&A

The coffin of Princess Sopdet-em-haawt is on view as part of Making Egypt, the major new exhibition at the Young V&A, running until 2 November 2025. The exhibition offers a rare chance to examine the coffin's beautifully preserved decoration up close, including the striking internal yellow and white stripes, and reflects on how ancient Egypt has influenced art, design and popular culture today.

The inner sarcophagus of Princess Sopdet-em-haawt on view as part of Making Egypt, Young V&A, 2025. Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Photo: David Parry

Notable Sale: Enigmacursor Joins the Natural History Museum

Published 25/06/2025

Read time: 2min

David Aaron is proud to announce the sale of a newly identified dinosaur species to the Natural History Museum, London. First exhibited at Frieze Masters in 2023, and identified as a Nanosaurus, this exceptional Late Jurassic skeleton has since been reclassified as a previously unknown species and genus, an Enigmacursor, which means “the enigmatic runner.”

"The sale of this extraordinary skeleton to the Natural History Museum is a true honour," says Salomon Aaron, director of David Aaron. "This specimen allows for further important research into what we understand about dinosaur species and adds a significant chapter to the Museum's rich tapestry of natural history."

The Enigmacursor on display at the Natural History Museum, London. (Image credit: Lucie Goodayle, The Natural History Museum)

Conservation and analysis of the Enigmarcusor taking place at the Natural History Museum (Image credit: The Natural History Museum)

"The sale of this extraordinary skeleton to the Natural History Museum is a true honour," says Salomon Aaron, director of David Aaron. "This specimen allows for further important research into what we understand about dinosaur species and adds a significant chapter to the Museum's rich tapestry of natural history."

The Enigmacursor on display at the Natural History Museum, London. (Image credit: Lucie Goodayle, The Natural History Museum)

Excavated in 2021–22 on the Skull Creek site in Moffat County, Colorado, the fossil quickly attracted attention for its completeness, detail and size. With a mounted length of just over 180 cm, it appeared at first to match descriptions of Nanosaurus, long considered one of the smallest dinosaurs of the Jurassic period.

But following in depth research led by the Natural History Museum’s palaeontology team, the specimen has now been confirmed as a distinct and newly recognised species. It is also thought there are signs that the dinosaur was not fully grown, says co-lead research author Professor Paul Barrett.

“One feature we look at in dinosaurs are the neural arches,” Paul explains. “These are the top section of vertebrae, and form separately from the lower parts. They gradually merge as an animal gets older, so by examining them you can see whether it was still growing.”

But following in depth research led by the Natural History Museum’s palaeontology team, the specimen has now been confirmed as a distinct and newly recognised species. It is also thought there are signs that the dinosaur was not fully grown, says co-lead research author Professor Paul Barrett.

“One feature we look at in dinosaurs are the neural arches,” Paul explains. “These are the top section of vertebrae, and form separately from the lower parts. They gradually merge as an animal gets older, so by examining them you can see whether it was still growing.”

Conservation and analysis of the Enigmarcusor taking place at the Natural History Museum (Image credit: The Natural History Museum)

The acquisition has received widespread media coverage, including features by the BBC and the Evening Standard to name a few. This important addition to the museum’s internationally respected dinosaur collection not only enriches our understanding of small herbivorous dinosaurs in the Late Jurassic but also underscores the dynamic nature of palaeontological research, where each discovery has the potential to reshape what we think we know.

We are honoured to have played a part in the journey of this rare fossil and proud to have helped it find its permanent home in the halls of the Natural History Museum.

We are honoured to have played a part in the journey of this rare fossil and proud to have helped it find its permanent home in the halls of the Natural History Museum.

Walking with Maple: A Real Triceratops in Mayfair

Published 27/05/2025

Read time: 3min

This Sunday marked the return of the BBC’s acclaimed natural history docuseries Walking with Dinosaurs, with the premiere of its second season. The episode followed Clover, a young triceratops navigating the perils of prehistoric North America, including a dramatic encounter with a fully grown Tyrannosaurus rex.

Dinosaurs, with their awe-inspiring scale and dramatic mass extinction, continue to capture the public imagination like few other subjects. They are both nostalgic and timeless, igniting a sense of wonder across generations. From popular culture to cutting-edge palaeontology, dinosaurs consistently draw global attention, both in science and the arts.

Among them, few are as instantly recognisable as the Triceratops. With its broad bony frill, parrot-like beak and three distinctive facial horns, it has become an icon of prehistoric life. The genus name means “three-horned face”, and the creature’s appearance is both formidable and strangely endearing.

The first known remains of a Triceratops were discovered in 1887 in Colorado. Initially believed to belong to a species of extinct bison, the fossilised horns were re-identified by American palaeontologist Othniel Charles Marsh, who formally described Triceratops horridus in 1889 and Triceratops prorsus in 1890. A fully mounted skeleton, named Hatcher, the first to go on display, was later unveiled by the Smithsonian Institution in 1905 and remains one of the centrepieces of their dinosaur collection.

Hatcher, the first mounted and exhibited Triceratops, went on display in 1905, Smithsonian Institution.

At our gallery on Berkeley Square, we are privileged to host a real Triceratops skull; an extraordinary specimen named Maple. Estimated to be from a sub-adult, nearing full maturity, Maple’s skull measures a remarkable 181 cm from jaw to frill. It is believed that Triceratops reached full maturity around ten years of age, making juvenile and subadult fossils particularly scarce.

Maple was discovered in 2019 in the fossil-rich badlands of Montana and excavated throughout 2020. Following discovery, the skull underwent meticulous preparation, including expert conservation and reconstruction.

Palaeontologists assess age not only by size but also by the development of certain cranial features such as epoccipitals, small bony projections that line the top edge of the frill. These ridges, along with bone texture and suture fusion, help scientists estimate growth stages and age at death.

We were honoured to exhibit Cera, a smaller juvenile Triceratops, closer in size to the BBC's Triceratops Clover at Frieze Masters in 2022, which had these epoccipital bones still visible, where it received notable attention, including a feature in The Art Newspaper. The overwhelming public and media interest affirmed what we already knew- dinosaurs are as culturally relevant today as they were 66 million years ago.

'Cera', A smaller example of a 'Juvenile Triceratops Skull' on show at Frieze Masters, London, in 2022. David Aaron Ltd

Triceratops is known for having had one of the largest skulls of any land animal in history. "It took up about a quarter of its whole body length, which is an unbelievably big skull," notes Dr Paul Barrett, palaeontologist at the Natural History Museum.

Today, fragments of Triceratops fossils are housed in museums and private collections around the world. However, few offer the opportunity to come face-to-face with a skull as complete and striking as Maple’s.

If you are in Mayfair, we welcome you to visit our gallery and experience this extraordinary piece of natural history in person. Maple is waiting.

Dinosaurs, with their awe-inspiring scale and dramatic mass extinction, continue to capture the public imagination like few other subjects. They are both nostalgic and timeless, igniting a sense of wonder across generations. From popular culture to cutting-edge palaeontology, dinosaurs consistently draw global attention, both in science and the arts.

Among them, few are as instantly recognisable as the Triceratops. With its broad bony frill, parrot-like beak and three distinctive facial horns, it has become an icon of prehistoric life. The genus name means “three-horned face”, and the creature’s appearance is both formidable and strangely endearing.

The first known remains of a Triceratops were discovered in 1887 in Colorado. Initially believed to belong to a species of extinct bison, the fossilised horns were re-identified by American palaeontologist Othniel Charles Marsh, who formally described Triceratops horridus in 1889 and Triceratops prorsus in 1890. A fully mounted skeleton, named Hatcher, the first to go on display, was later unveiled by the Smithsonian Institution in 1905 and remains one of the centrepieces of their dinosaur collection.

Hatcher, the first mounted and exhibited Triceratops, went on display in 1905, Smithsonian Institution.

At our gallery on Berkeley Square, we are privileged to host a real Triceratops skull; an extraordinary specimen named Maple. Estimated to be from a sub-adult, nearing full maturity, Maple’s skull measures a remarkable 181 cm from jaw to frill. It is believed that Triceratops reached full maturity around ten years of age, making juvenile and subadult fossils particularly scarce.

Maple was discovered in 2019 in the fossil-rich badlands of Montana and excavated throughout 2020. Following discovery, the skull underwent meticulous preparation, including expert conservation and reconstruction.

Palaeontologists assess age not only by size but also by the development of certain cranial features such as epoccipitals, small bony projections that line the top edge of the frill. These ridges, along with bone texture and suture fusion, help scientists estimate growth stages and age at death.

We were honoured to exhibit Cera, a smaller juvenile Triceratops, closer in size to the BBC's Triceratops Clover at Frieze Masters in 2022, which had these epoccipital bones still visible, where it received notable attention, including a feature in The Art Newspaper. The overwhelming public and media interest affirmed what we already knew- dinosaurs are as culturally relevant today as they were 66 million years ago.

'Cera', A smaller example of a 'Juvenile Triceratops Skull' on show at Frieze Masters, London, in 2022. David Aaron Ltd

Triceratops is known for having had one of the largest skulls of any land animal in history. "It took up about a quarter of its whole body length, which is an unbelievably big skull," notes Dr Paul Barrett, palaeontologist at the Natural History Museum.

Today, fragments of Triceratops fossils are housed in museums and private collections around the world. However, few offer the opportunity to come face-to-face with a skull as complete and striking as Maple’s.

If you are in Mayfair, we welcome you to visit our gallery and experience this extraordinary piece of natural history in person. Maple is waiting.

Maple, Sub-adult Triceratops Skull, Maastrichtian, Late Cretaceous Period (circa 68 million years ago), Fossilised Bone, Frill width: 119 cm, Length from top of frill to tip of jaw: 181cm, Horn length: 30 cm, Height on stand: 241 cm. David Aaron Ltd

TEFAF NY: A Successful Debut

Published 16/05/2025

Read time: 2min

Over the past week, we have been making our debut at TEFAF New York. As first-time exhibitors at this prestigious art fair, we have been very delighted with the reception. The historic Park Avenue Armory provided an excellent setting for the carefully curated group of antiquities we selected for the fair.

Our exhibition began successfully with the sale of the 'Hultmark Horus', an exceptional Egyptian bronze falcon. The piece attracted significant attention from art collectors and the media prior to opening day. This interest resulted in its sale for £520,000 during the collector's preview. The hollow-cast bronze falcon served as a votive offering and possibly a ceremonial object during 663-525 B.C. in ancient Egypt. It was previously in the Private collection of Swedish collector Dr. Emil Hultmark (1872-1943), and the piece was photographed in his home in 1942.

The Hultmark Horus, 663-525 B.C., Saitic Period, Egypt, Bronze, H: 22.7 cm. David Aaron Ltd

The Hultmark Horus, 663-525 B.C., Saitic Period, Egypt, Bronze, H: 22.7 cm. David Aaron Ltd

It was a particularly rewarding experience for us to bring such an important example of ancient Egyptian culture to New York "Being part of TEFAF's elite roster of exhibitors has been an amazing experience," noted Director Salomon Aaron. "The response to our collection has exceeded our expectations, and we appreciate the warm welcome from the New York art community."

We would like to thank the TEFAF organising committee for hosting another fantastic art show; Jitske Nap for the excellent photographs; the vetting committee for their professionalism; the stand-builders and shipping agents; the press team for coordinating our media interactions; and all the TEFAF staff who worked throughout the week and contributed to the quality of the experience.

David Aaron, Stand 212, TEFAF NY, 2025. David Aaron Ltd

Our exhibition began successfully with the sale of the 'Hultmark Horus', an exceptional Egyptian bronze falcon. The piece attracted significant attention from art collectors and the media prior to opening day. This interest resulted in its sale for £520,000 during the collector's preview. The hollow-cast bronze falcon served as a votive offering and possibly a ceremonial object during 663-525 B.C. in ancient Egypt. It was previously in the Private collection of Swedish collector Dr. Emil Hultmark (1872-1943), and the piece was photographed in his home in 1942.

The Hultmark Horus, 663-525 B.C., Saitic Period, Egypt, Bronze, H: 22.7 cm. David Aaron Ltd

The Hultmark Horus, 663-525 B.C., Saitic Period, Egypt, Bronze, H: 22.7 cm. David Aaron Ltd

It was a particularly rewarding experience for us to bring such an important example of ancient Egyptian culture to New York "Being part of TEFAF's elite roster of exhibitors has been an amazing experience," noted Director Salomon Aaron. "The response to our collection has exceeded our expectations, and we appreciate the warm welcome from the New York art community."

We would like to thank the TEFAF organising committee for hosting another fantastic art show; Jitske Nap for the excellent photographs; the vetting committee for their professionalism; the stand-builders and shipping agents; the press team for coordinating our media interactions; and all the TEFAF staff who worked throughout the week and contributed to the quality of the experience.

David Aaron, Stand 212, TEFAF NY, 2025. David Aaron Ltd

The Artist as Collector: Jacob Epstein

Published 08/05/2025

Read time: 5min

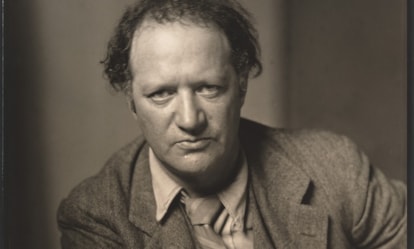

Sir Jacob Epstein was born on New York’s Lower East Side in 1880, the third son to Polish Jewish immigrant parents. He developed an interest in drawing due to long periods of illness caused by pleurisy in his childhood. He began studying at the Arts Students’ League from the age of thirteen. At first, Epstein made his living by working in a bronze foundry, but he continued to take evening classes in sculpting. His first major commission was to illustrate Hutchins Hapgood’s 1902 book The Spirit of The Ghetto, and he used his earnings from this to move to Paris that same year.

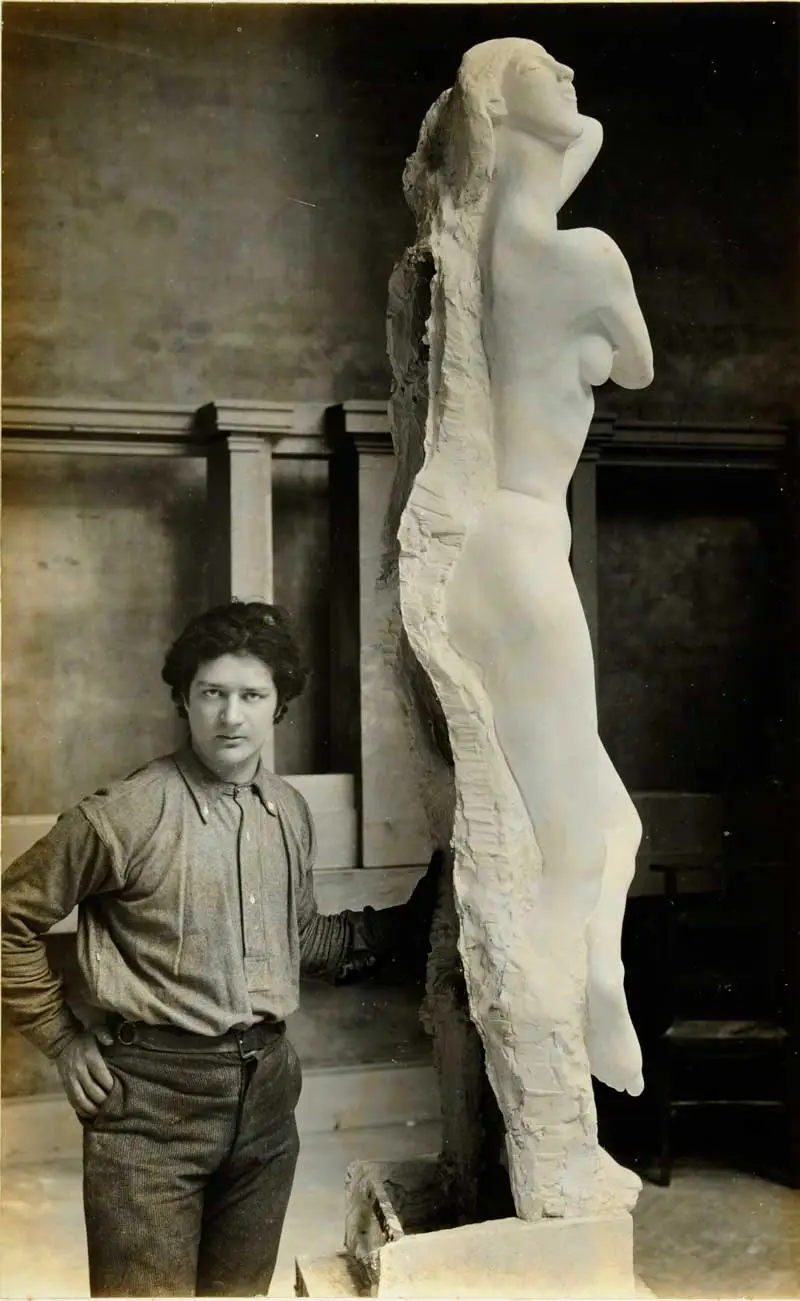

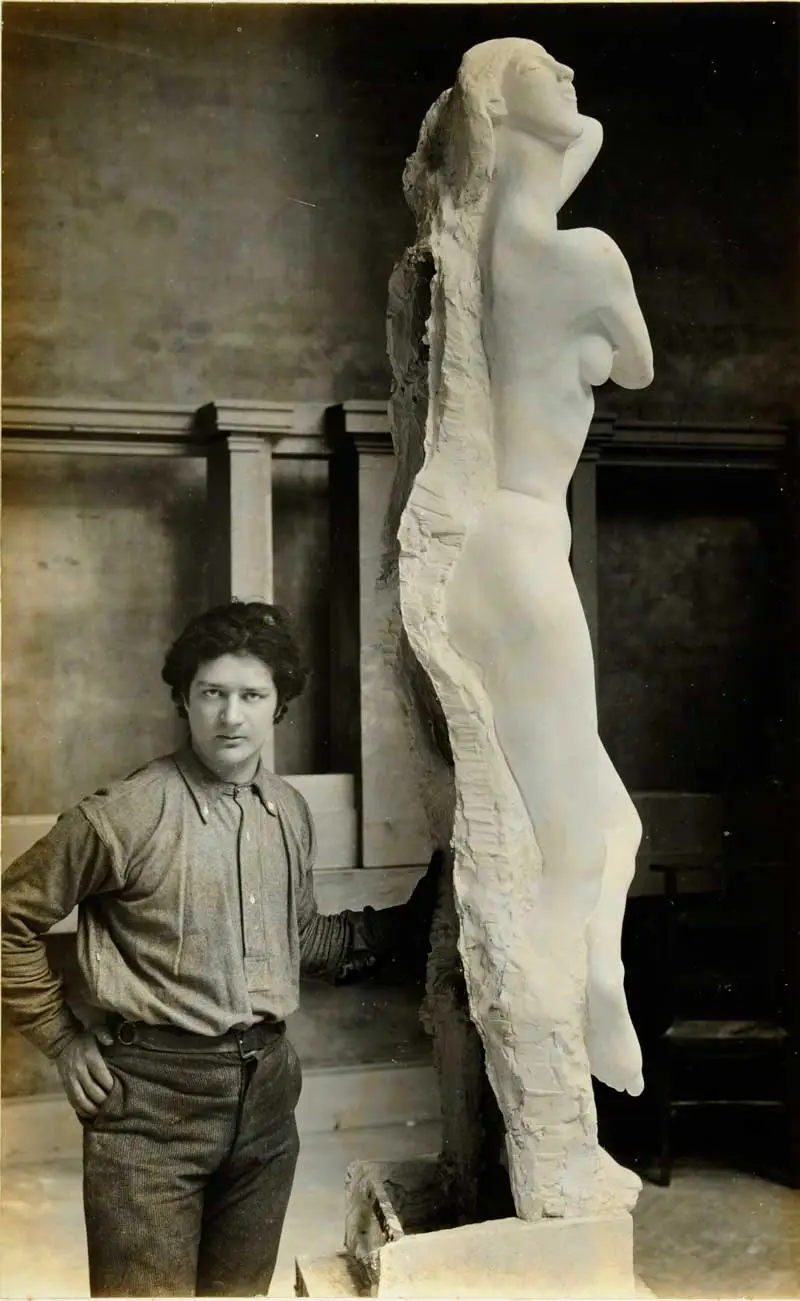

Jacob Epstein at work on one of the statues for the British Medical Association building, The Sketch (8 July 1908)

In Paris, Epstein studied sculpture at the Académie Julian and the École des Beaux-Arts; though his studies ended prematurely at the latter after his studio was destroyed as punishment for his refusal to perform menial tasks for the entrants in the Prix de Rome Concours. He visited the Louvre and saw artworks from outside the Western canon that were less known in Europe at that time, including early Greek work, Cycladic sculpture, the Lady of Elche bust, and the limestone bust of Akhenaten. At the Trocadéro and the Musée Cernusci, he observed what was then known as ‘primitive’ sculpture and Chinese art. In 1905, Epstein moved to London, where he would live for most of the rest of his life – he married Margaret Dunlop in 1906, and took British citizenship in 1911. Epstein spent a great deal of time in the British Museum, studying the Elgin Marbles and other Greek, Egyptian, African, and Polynesian sculptures, and used his observations to develop his own sculptural technique.

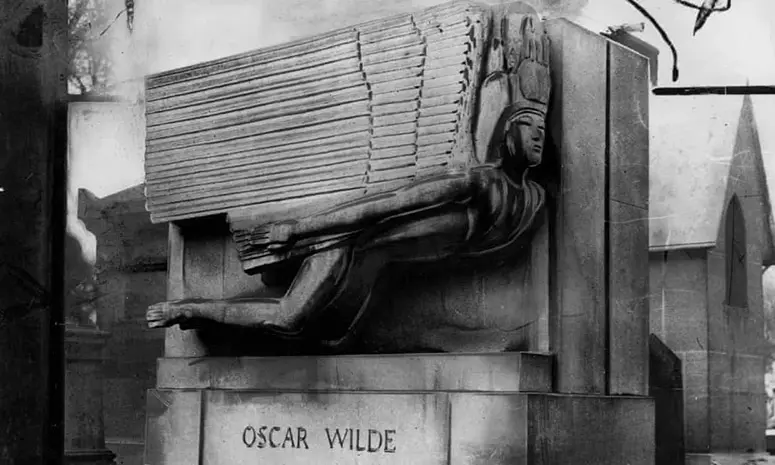

In 1907-8, Epstein was invited by architect Charles Holden to carve eighteen over-life-size figures for the façade of the British Medical Association’s new headquarters in The Strand. For this work, Epstein drew from the ancient and ‘primitive’ works he had studied, and suggested a series of nudes, ‘to express in sculpture the great primal facts of men and women’. According to his 1940 autobiography, Let There Be Sculpture, Epstein was taken completely by surprise at the level of vitriol and controversy sparked by this commission. Though many known figures and artists defended his pieces, public outcry made Epstein a household name and was to follow him throughout his career. For instance, the tomb he carved with Eric Gill for Oscar Wilde in Paris in 1911-12 and his 1915 Rock Drill sculpture prompted similar responses. One critic described Epstein as ‘a sculptor in revolt, who is in deadly conflict with the ideas of current sculpture’. His contemporary Henry Moore praised Epstein for unflinchingly bearing the weight of prejudice and hostility to forge a path for those sculptors who followed him, and expressed great gratitude for Epstein’s courage.

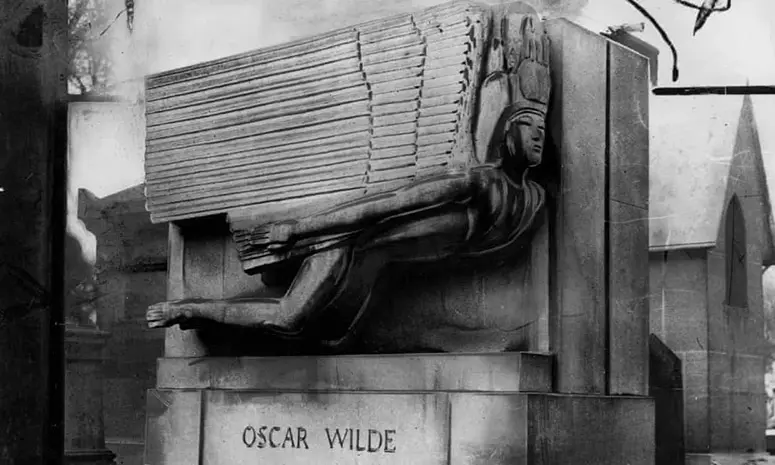

Oscar Wilde's tomb, located in Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris.

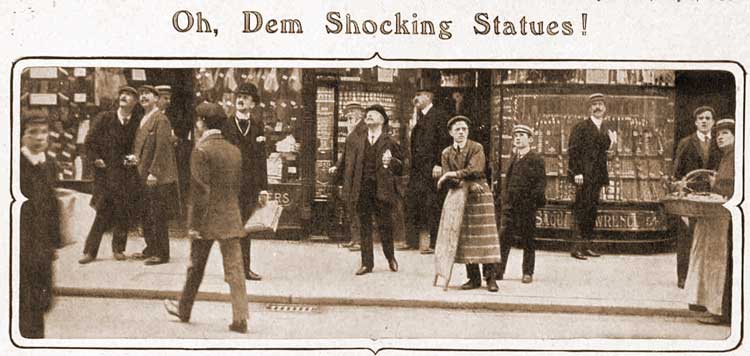

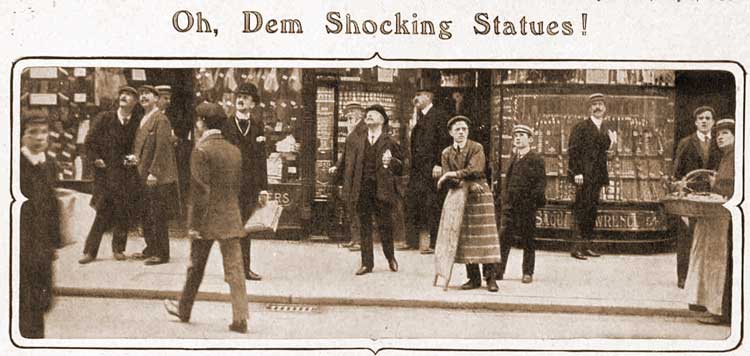

‘Pedestrians on the Strand eagerly gazing up at the building of the British Medical Association, in search of the statues which the papers said were rather shocking and ought to be suppressed.’ From The Bystander (1st July, 1908).

Three nude male figures from the Ages of Man series, former British Medical Association building, now Zimbabwe House, The Strand, London.

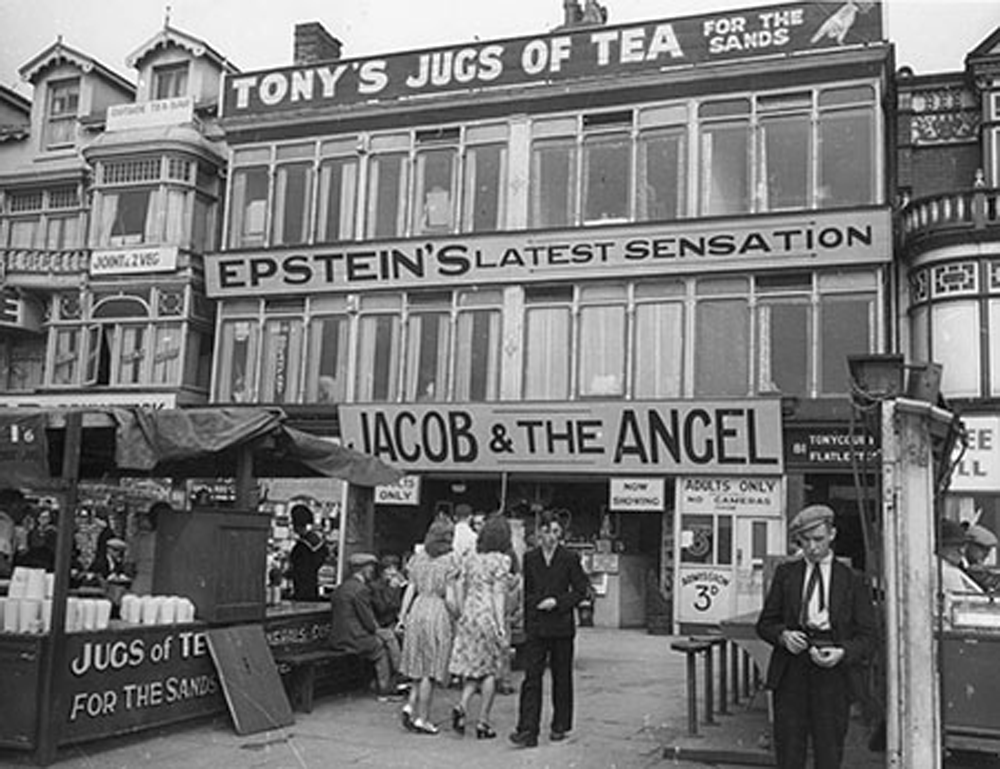

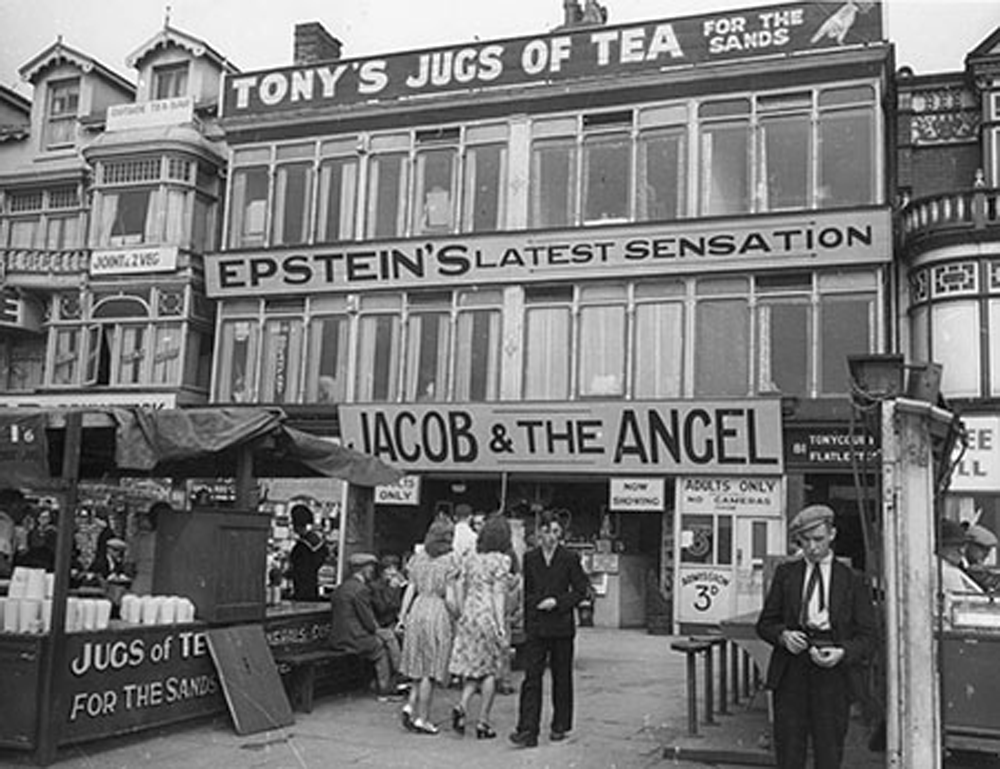

Signs advertising Epstein’s Jacob and the Angel (1940-1) at Louis Tussaud’s Waxworks, Blackpool

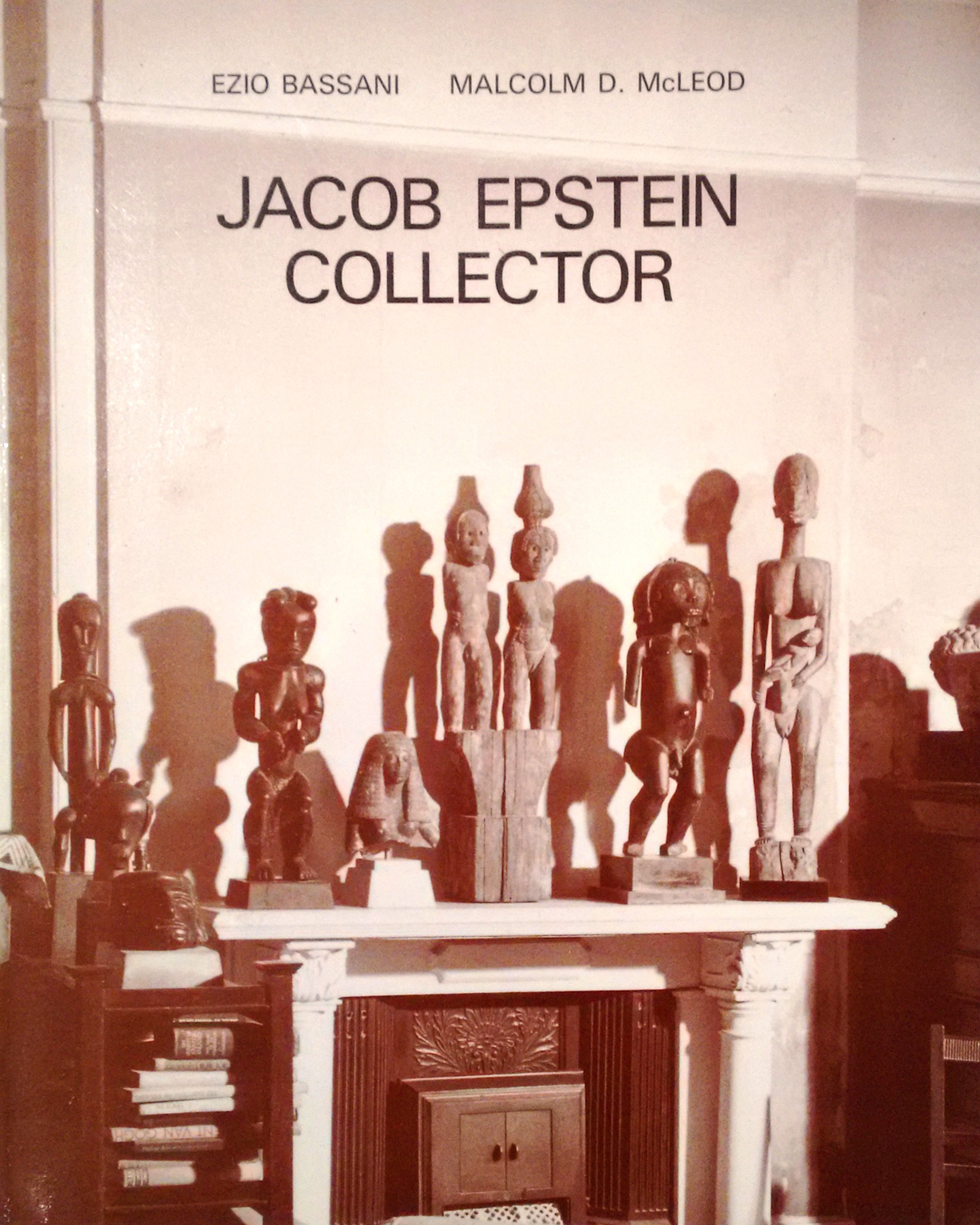

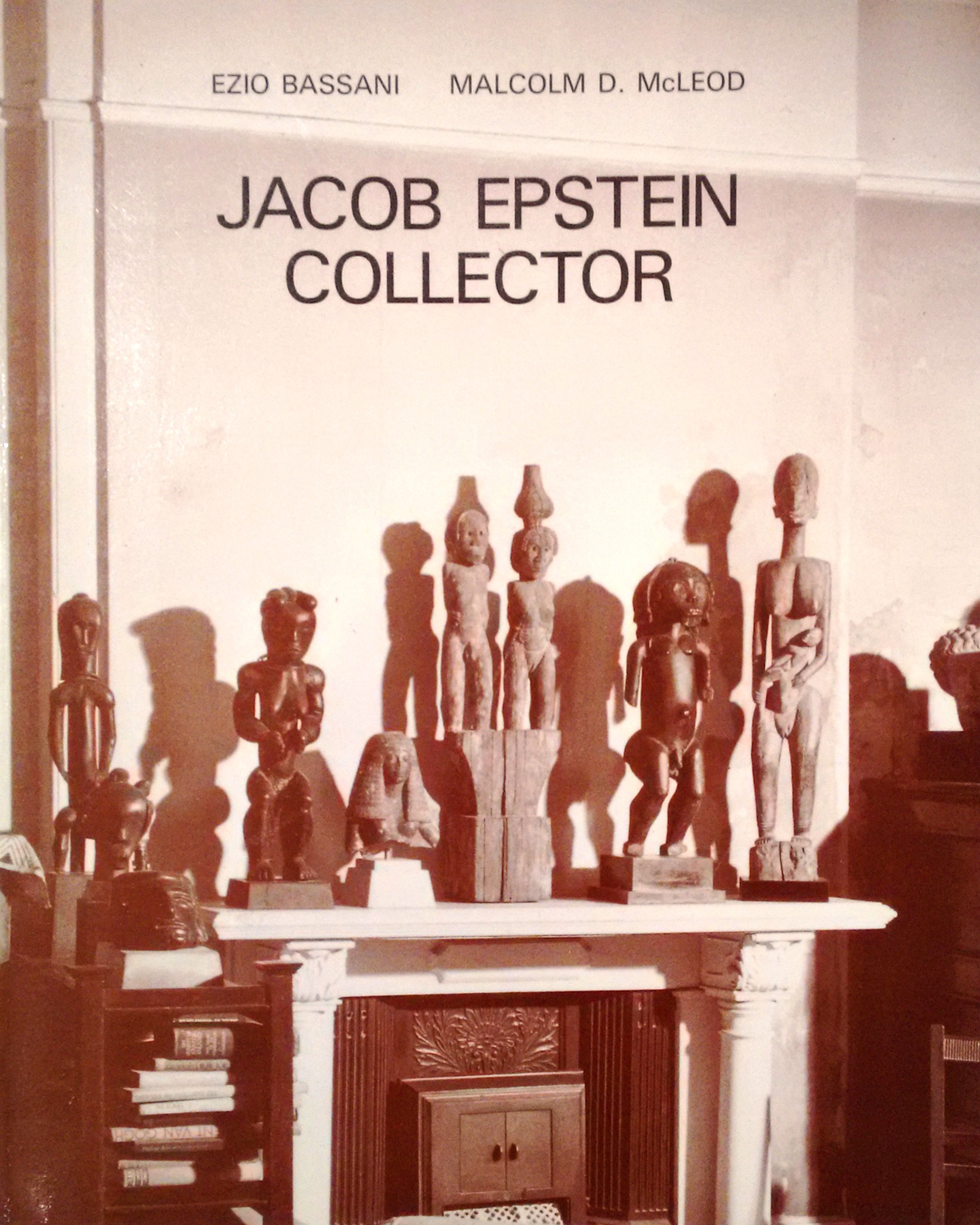

'Jacob Epstein Collector', front cover showing the interior of Epstein's home and some of his collection of African art. Published by Associazione Poro (Milan, Italy, 1989)

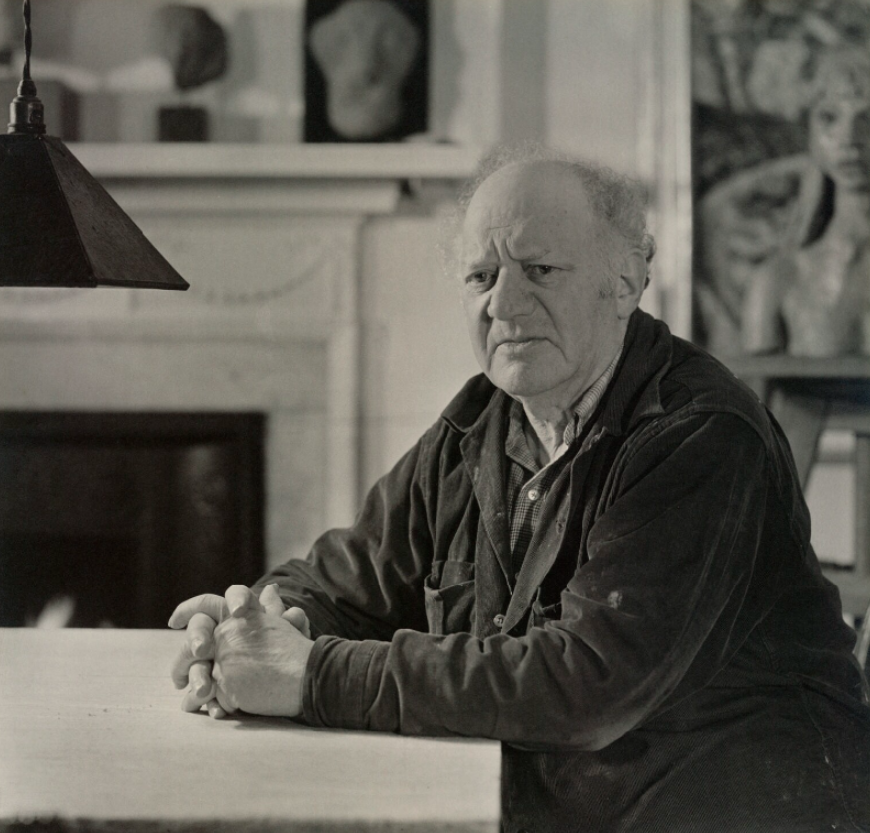

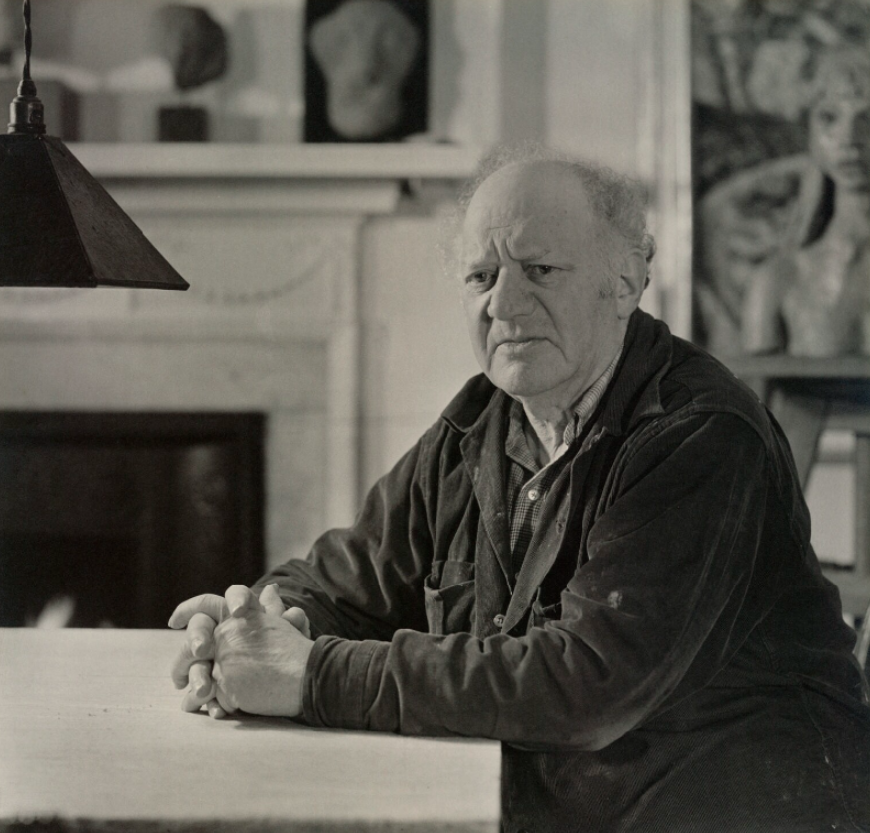

Portrait of Jacob Epstein, Geoffrey Ireland. Ancient Egyptian items from Epstein’s collection can be seen on the mantlepiece behind him. National Portrait Gallery.

Pregnant Cycladic Idol, 2500-2000 B.C., Greece, Marble, H: 14.5 cm, previously in the Private Collection of Sir Jacob Epstein. David Aaron Ltd

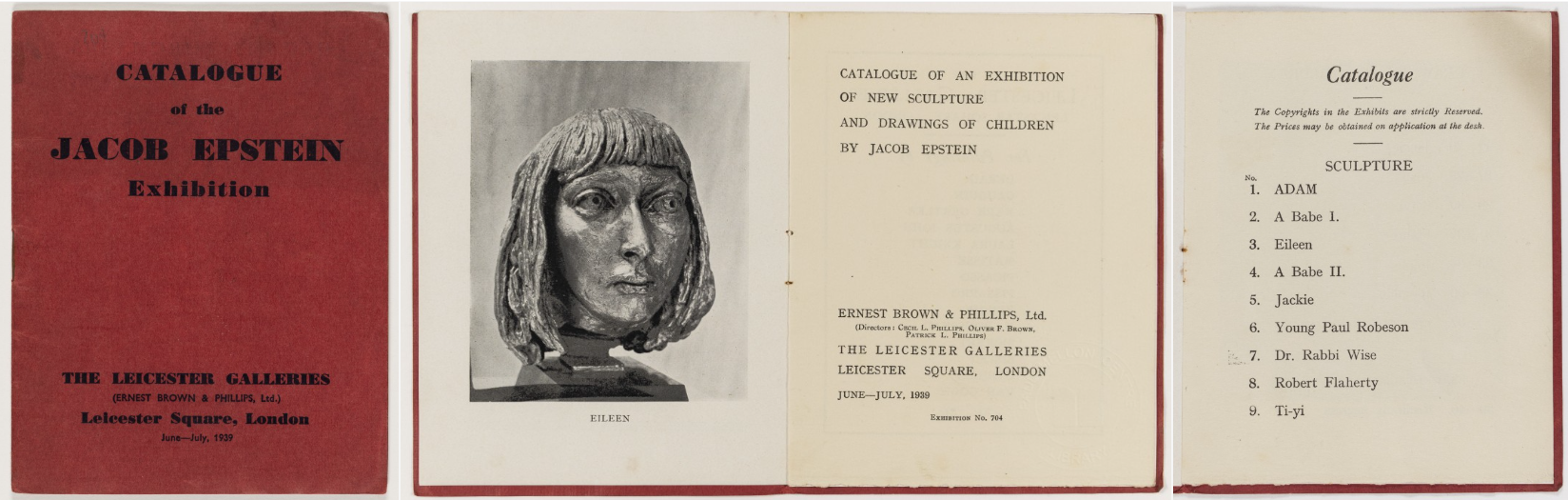

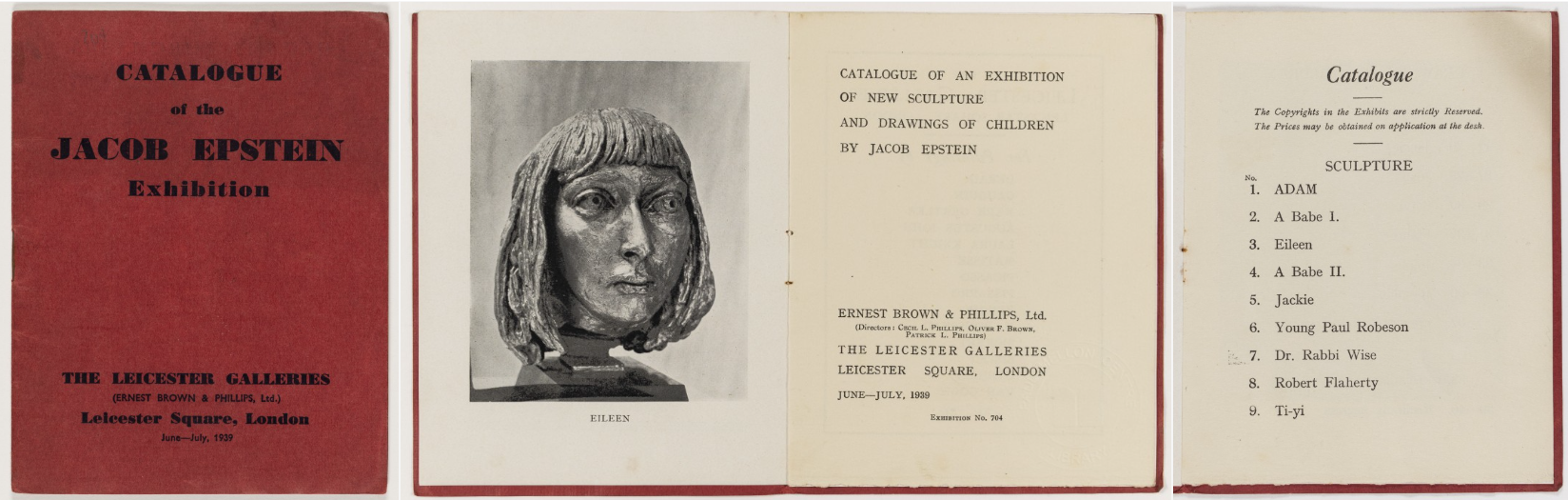

In the 1939 exhibition catalogue, Epstein showcased multiple works, including busts of children and the sculpture of 'ADAM'.

The monumental sculpture of 'ADAM' was later on show in Blackpool. The exhibition received mixed reviews, and a Pathé newsreel shows crowds attending, including a woman fainting.

Cycladic Idol, 2500-2000 B.C., Greece, Marble, H: 21.4 cm, previously in the Private Collection of Sir Jacob Epstein. David Aaron Ltd.

Jacob Epstein at work on one of the statues for the British Medical Association building, The Sketch (8 July 1908)

In Paris, Epstein studied sculpture at the Académie Julian and the École des Beaux-Arts; though his studies ended prematurely at the latter after his studio was destroyed as punishment for his refusal to perform menial tasks for the entrants in the Prix de Rome Concours. He visited the Louvre and saw artworks from outside the Western canon that were less known in Europe at that time, including early Greek work, Cycladic sculpture, the Lady of Elche bust, and the limestone bust of Akhenaten. At the Trocadéro and the Musée Cernusci, he observed what was then known as ‘primitive’ sculpture and Chinese art. In 1905, Epstein moved to London, where he would live for most of the rest of his life – he married Margaret Dunlop in 1906, and took British citizenship in 1911. Epstein spent a great deal of time in the British Museum, studying the Elgin Marbles and other Greek, Egyptian, African, and Polynesian sculptures, and used his observations to develop his own sculptural technique.

In 1907-8, Epstein was invited by architect Charles Holden to carve eighteen over-life-size figures for the façade of the British Medical Association’s new headquarters in The Strand. For this work, Epstein drew from the ancient and ‘primitive’ works he had studied, and suggested a series of nudes, ‘to express in sculpture the great primal facts of men and women’. According to his 1940 autobiography, Let There Be Sculpture, Epstein was taken completely by surprise at the level of vitriol and controversy sparked by this commission. Though many known figures and artists defended his pieces, public outcry made Epstein a household name and was to follow him throughout his career. For instance, the tomb he carved with Eric Gill for Oscar Wilde in Paris in 1911-12 and his 1915 Rock Drill sculpture prompted similar responses. One critic described Epstein as ‘a sculptor in revolt, who is in deadly conflict with the ideas of current sculpture’. His contemporary Henry Moore praised Epstein for unflinchingly bearing the weight of prejudice and hostility to forge a path for those sculptors who followed him, and expressed great gratitude for Epstein’s courage.

Oscar Wilde's tomb, located in Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris.

‘Pedestrians on the Strand eagerly gazing up at the building of the British Medical Association, in search of the statues which the papers said were rather shocking and ought to be suppressed.’ From The Bystander (1st July, 1908).

Three nude male figures from the Ages of Man series, former British Medical Association building, now Zimbabwe House, The Strand, London.

After the First World War, Epstein received relatively few commissions, although his notoriety continued. Between the 1930s and mid-1950s, some of Epstein’s sculptures were exhibited within the anatomical curiosity section of Louis Tussaud’s waxworks, alongside diseased body parts and conjoined twin babies preserved in jars. Epstein’s bronze portraits were received more favourably; these depicted a range of figures, from his mistress and later wife Kathleen Garman, to Albert Einstein, to ragamuffin children. In the 1950s, Epstein received some important public commissions, including the statue of Jan Smuts in Parliament Square. Epstein was appointed a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire in the 1954 New Year Honours. In 1958, Epstein was confined to hospital due to illness, but continued to work even up to the day of his death in 1959.

Signs advertising Epstein’s Jacob and the Angel (1940-1) at Louis Tussaud’s Waxworks, Blackpool

'Jacob Epstein Collector', front cover showing the interior of Epstein's home and some of his collection of African art. Published by Associazione Poro (Milan, Italy, 1989)

Sculptural Bust from a Reliquary Ensemble (The Great Bieri), 19th century, Wood and copper alloy, H46.5cm. Previously in the private collection of Jacob Epstein, now with the Metropolitan Museum, NY, USA.

Epstein dated the start of his collection of African sculpture to around 1905 – the same time that Picasso, Vlaminck, and Matisse began to express their interest in such pieces, putting him at the forefront of Western interest in ‘primitive’ art. The dealer Paul Guillaume, writing in 1917, described Epstein as ‘le promoteur’ of African art in England. In 1924, Henry Moore visited Epstein’s house in Hyde Park Gate, and remarked that his bedroom ‘was so overflowing with negro sculpture etc., that I wondered how he got into bed without knocking something over’. By the time Arnold Haskell interviewed the artist in 1931, Epstein had around 200 statues, masks, and ivories. Each week during his conversations with Haskell, Epstein would rearrange the room with different items from his collection. By Haskell’s account ‘This is certainly the finest private collection in England, and one of the finest in the world. Each piece is the work of some remarkable unknown artist, and there are few, very few, ‘mistakes’ amongst them … There is none of the deadness of the museum here, and the works have not lost their individuality.’[1] Epstein himself took great pride in his collection, asserting that his possessions were superior to or more authentic than others’.

Portrait of Jacob Epstein, Geoffrey Ireland. Ancient Egyptian items from Epstein’s collection can be seen on the mantlepiece behind him. National Portrait Gallery.

Pregnant Cycladic Idol, 2500-2000 B.C., Greece, Marble, H: 14.5 cm, previously in the Private Collection of Sir Jacob Epstein. David Aaron Ltd

Epstein collected with great voracity, often acquiring pieces before he had money in hand to pay for them (several of these debts were only paid off after his death). He eventually had over 1,000 pieces in his collection at Hyde Park Gate. Although Epstein’s name rarely appears in the price lists of auction houses like Sotheby’s, he is known to have purchased items through a range of avenues, including the London dealer John Hewett, and Galerie Apollinaire. He was persistent in chasing what he felt were quality pieces – for instance, he first enquired about the ‘Brummer Head’ while it was still in the possession of Joseph Brummer well before 1913, and eventually purchased it in 1935 when he discovered it in a dealer’s basement. Epstein also advised other collectors of African art, including Helena Rubinstein, whom he met in 1909.

Epstein professed that he was not interested in works for their ethnographical import, but for their artistic and formal qualities. He claimed he had two collections: one with the best works of art he could find on the market, and one he made for himself as an artist, of lesser works that gave him new ideas around formal issues. Epstein praised the ‘restraint in craftsmanship, delicacy and sensitiveness, [and] regard for the material’ he saw in ‘primitive’ sculpture.[1] Epstein’s own work, such as Female Figure in Flenite (1913) and Venus (1917), incorporated the simple yet evocative forms that he admired in non-Western figures.

In the 1939 exhibition catalogue, Epstein showcased multiple works, including busts of children and the sculpture of 'ADAM'.

The monumental sculpture of 'ADAM' was later on show in Blackpool. The exhibition received mixed reviews, and a Pathé newsreel shows crowds attending, including a woman fainting.

After Epstein’s death in 1959, the Arts Council held a memorial exhibition featuring most of the works from his collection. In 1963, Carlo Monzino bought the major part of the collection, in what he described as ‘the culminating moment for me’. Since then, works from Epstein’s collection have gone on to sell for record-breaking prices and are found in museums around the world. The British Museum has twelve objects from his collection, all purchased in the sale at Christie’s, 15 December 1961, while the Metropolitan Museum has nine, and others are with The Dapper Foundation, Paris.

Cycladic Idol, 2500-2000 B.C., Greece, Marble, H: 21.4 cm, previously in the Private Collection of Sir Jacob Epstein. David Aaron Ltd.

Corsican Bronzes: One-Way Track to the Past

Published 08/05/2025

Read time: 3min

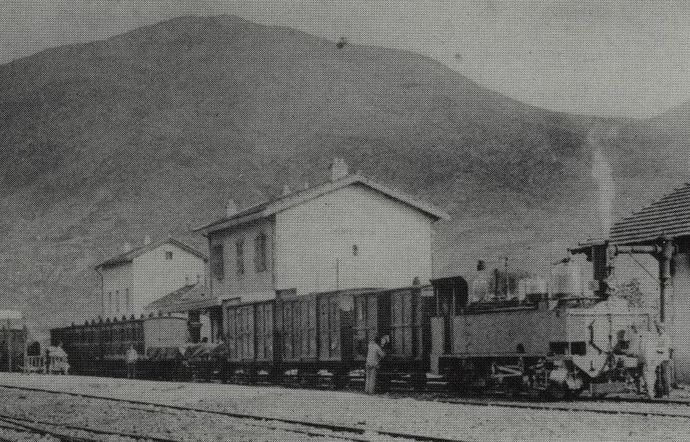

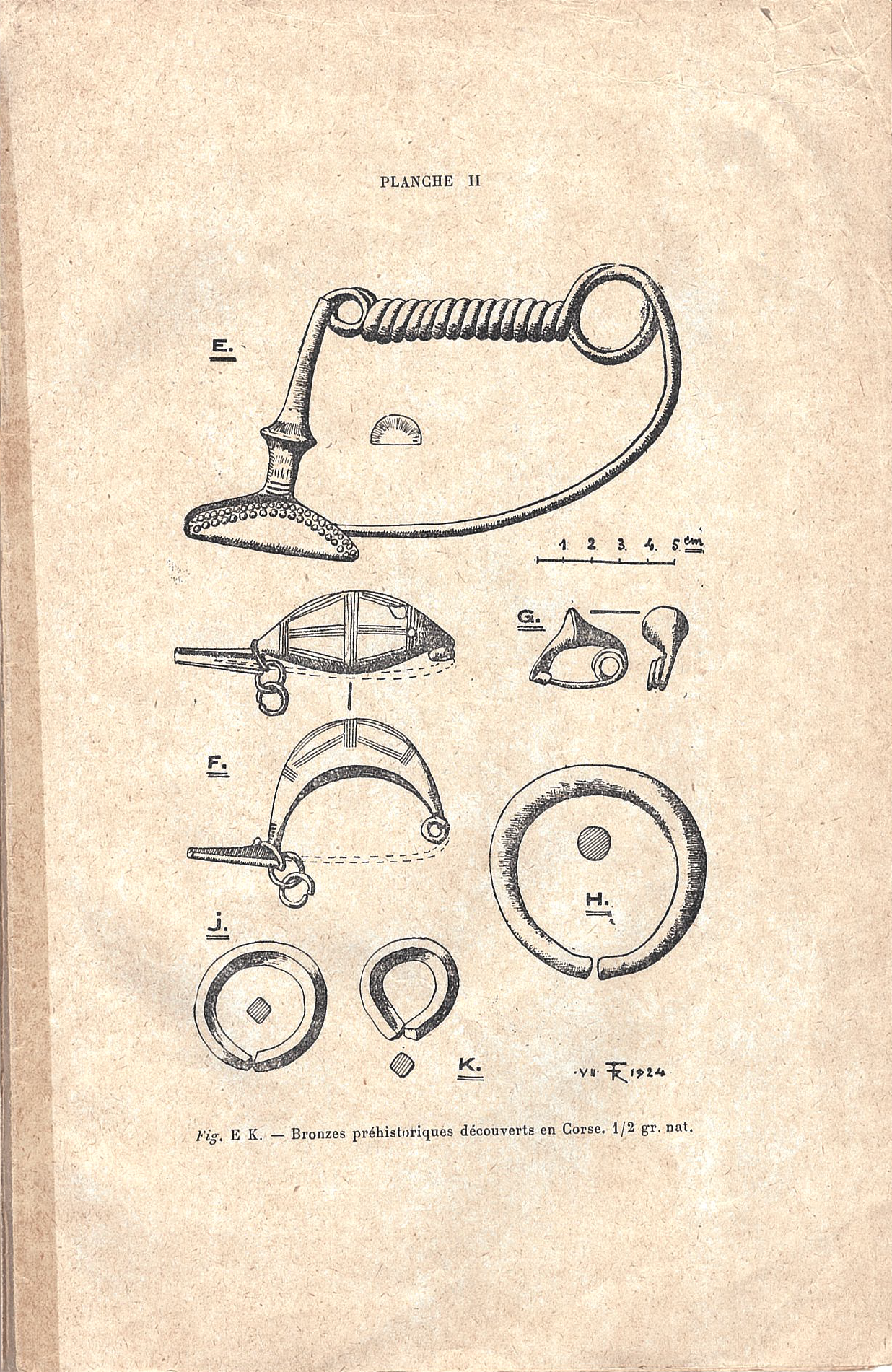

This collection of bronze implements were discovered at the same site on the bed of the Gravona river in Corsica around 1888-1890. They were found during the construction of the Ajaccio-Bastia railway line, which first opened in 1888. This enables us to pinpoint their location to one of two possible sites where the railway crosses the river: either in Carbuccia, 10 km north-east of Ajaccio, or at Bocognano, 10 km further in the same direction along the valley.

Connecting trains in Ponte-Leccia station. Mixed right for Ajaccio towed by a 031 Fives-Lille locomotive, circa 1882 (Collection J.RENAUD)

The group contains:

-one dagger

-one crescent-shaped bronze that may have been a belt-buckle

-one rounded pommel

-one disc with a projecting spike, which may have been part of a horses harness or brooch

-three bow fibulae (brooches) of various sizes

-three simple rings of differing sizes, possibly a form of proto-currency.

The style of these objects suggests a burial date of around 900 BCE. Then-director of the Musée préhistorique et gallo-romain in Strasbourg, Dr. Robert Forrer, published this group in an 8-page essay in the bulletin of the Société Préhistorique Française in 1924.

R Forrer, ‘Un trésor de bronzes préhistoriques decouvert en Corse’, Bulletin de la Société préhistorique de France, 10, 1924, pp. 224-232.

Why were these pieces buried together?

It is clear that these pieces were intentionally buried as a group by someone in ancient history. What is not clear is why. One theory is that they formed part of a funerary hoard, perhaps together with several other buried objects along the banks of the Gravona. Another is that they were a trader’s wares or a warrior’s treasure and were buried for safekeeping.

The two possible discovery sites along the river are both in inland mountainous regions. Forrer’s theory was that the bronzes were brought in from Sardinia, via Ajaccio and up the river, and were the property of a Sherden warrior. However, recent research indicates that the Torrean civilisation in the south of Corsica – previously thought to have begun in the second millennium B.C. when Sherden warriors landed on the island – was in fact an indigenous population. There is at least one confirmed example of the distinctive megalithic towers (torri) built by this civilisation in the Gravona valley, north-east of the capital. Therefore, these bronzes may have been produced near the discovery site.

What are they?

Some of the bronzes require no explanation, such as the dagger in typical late Bronze Age style, and the fibulae, which closely resemble similar brooches now in major museums.

Some of the pieces are, however, less easily understood. One is the crescent-shaped object adorned with five evenly-spaced raised round rivets, a short cross with rounded ends extends from the inner centre of the arc. The rivets and hook could have served as a means of affixing the bronze in place, suggesting that this object may have been a belt buckle, or perhaps part of a scabbard or horse harness.

Another is the circular disc, with a large, rounded spike projecting from its centre. This form resembles the shields held by warriors in Nuragic bronze statues, possibly linking the pieces to the Sardinian warriors from Forrer’s theory. Small holes are pierced around the circumference, four of which contain chain links, suggesting that this disc was previously part of a larger object. The disc may have been a phalera on a horse harness or perhaps the centrepiece of a brooch, as in a contemporaneous example in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (2007.498.2).

The small pommel in the form of a hollow ovoid has one hole running through its length and another smaller hold at the side. These would allow a stick to be inserted through the pommel and held in place by a small nail, so that the pommel could be wielded as a part of a sceptre or other weapon. As it weighs in at a very light 69 grams, however, it seems most likely that the pommel would have been purely decorative – an ancient warrior wouldn’t have been able to do much damage with a 3.7 cm bronze!

Most puzzling are the three rings, each formed from a single bronze rod bent into a circle. Although they resemble Bronze Age bracelets from other sites, the largest is only 7.7 cm in diameter, and the others are much smaller, at 4.8 cm and 3.7 cm. These smallest two, would definitely not fit over anyone’s wrist. Forrer suggested one possible explanation of their purpose. He argued that, due to their simple forms and the relationships between their weights (the weight of the smallest is about 2/3 of the second smallest, which is approximately 1/4 of the largest), these rings may have been a form of currency, of the kind found in other Bronze Age settlements in Europe.

The Corsican Hoard raises many questions about the ancient society that produced it. We can only speculate as to who owned the pieces and why they were buried, and what purpose the bronzes served. Perhaps they hold the key to unravelling the secrets of Bronze Age Corsica.

Connecting trains in Ponte-Leccia station. Mixed right for Ajaccio towed by a 031 Fives-Lille locomotive, circa 1882 (Collection J.RENAUD)

The group contains:

-one dagger

-one crescent-shaped bronze that may have been a belt-buckle

-one rounded pommel

-one disc with a projecting spike, which may have been part of a horses harness or brooch

-three bow fibulae (brooches) of various sizes

-three simple rings of differing sizes, possibly a form of proto-currency.

The style of these objects suggests a burial date of around 900 BCE. Then-director of the Musée préhistorique et gallo-romain in Strasbourg, Dr. Robert Forrer, published this group in an 8-page essay in the bulletin of the Société Préhistorique Française in 1924.

R Forrer, ‘Un trésor de bronzes préhistoriques decouvert en Corse’, Bulletin de la Société préhistorique de France, 10, 1924, pp. 224-232.

Why were these pieces buried together?

It is clear that these pieces were intentionally buried as a group by someone in ancient history. What is not clear is why. One theory is that they formed part of a funerary hoard, perhaps together with several other buried objects along the banks of the Gravona. Another is that they were a trader’s wares or a warrior’s treasure and were buried for safekeeping.

The two possible discovery sites along the river are both in inland mountainous regions. Forrer’s theory was that the bronzes were brought in from Sardinia, via Ajaccio and up the river, and were the property of a Sherden warrior. However, recent research indicates that the Torrean civilisation in the south of Corsica – previously thought to have begun in the second millennium B.C. when Sherden warriors landed on the island – was in fact an indigenous population. There is at least one confirmed example of the distinctive megalithic towers (torri) built by this civilisation in the Gravona valley, north-east of the capital. Therefore, these bronzes may have been produced near the discovery site.

What are they?

Some of the bronzes require no explanation, such as the dagger in typical late Bronze Age style, and the fibulae, which closely resemble similar brooches now in major museums.

Some of the pieces are, however, less easily understood. One is the crescent-shaped object adorned with five evenly-spaced raised round rivets, a short cross with rounded ends extends from the inner centre of the arc. The rivets and hook could have served as a means of affixing the bronze in place, suggesting that this object may have been a belt buckle, or perhaps part of a scabbard or horse harness.

Another is the circular disc, with a large, rounded spike projecting from its centre. This form resembles the shields held by warriors in Nuragic bronze statues, possibly linking the pieces to the Sardinian warriors from Forrer’s theory. Small holes are pierced around the circumference, four of which contain chain links, suggesting that this disc was previously part of a larger object. The disc may have been a phalera on a horse harness or perhaps the centrepiece of a brooch, as in a contemporaneous example in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (2007.498.2).

Sardinian Warrior, 7th to 6th Century B.C, Bronze, H:16 cm. David Aaron Ltd.

The small pommel in the form of a hollow ovoid has one hole running through its length and another smaller hold at the side. These would allow a stick to be inserted through the pommel and held in place by a small nail, so that the pommel could be wielded as a part of a sceptre or other weapon. As it weighs in at a very light 69 grams, however, it seems most likely that the pommel would have been purely decorative – an ancient warrior wouldn’t have been able to do much damage with a 3.7 cm bronze!

Most puzzling are the three rings, each formed from a single bronze rod bent into a circle. Although they resemble Bronze Age bracelets from other sites, the largest is only 7.7 cm in diameter, and the others are much smaller, at 4.8 cm and 3.7 cm. These smallest two, would definitely not fit over anyone’s wrist. Forrer suggested one possible explanation of their purpose. He argued that, due to their simple forms and the relationships between their weights (the weight of the smallest is about 2/3 of the second smallest, which is approximately 1/4 of the largest), these rings may have been a form of currency, of the kind found in other Bronze Age settlements in Europe.

The Corsican Hoard raises many questions about the ancient society that produced it. We can only speculate as to who owned the pieces and why they were buried, and what purpose the bronzes served. Perhaps they hold the key to unravelling the secrets of Bronze Age Corsica.

The Attraction of Abstract Idols

Published 07/05/2025

Read time: 3min

Among the most enigmatic and compelling objects in the field of ancient art are abstract idols: small, stylised human figures, often reduced to the barest essentials of form, yet charged with a cultural, spiritual and aesthetic potency. These portable sculptures, ranging from the minimalist Cycladic figures of the Aegean to the alien-looking Mesopotamian Eye Idols, continue to fascinate not only archaeologists and historians, but also collectors, curators and contemporary artists.

Monumental Cycladic Torso of an Idol, possibly by the Copenhagen Master, 2500-2000 B.C., Bronze Age, Greece, Marble, H: 32 cm. David Aaron Ltd

The enduring appeal of such figures lies partly in their ambiguity. Whether carved in marble, stone or formed from terracotta, these objects resist precise interpretation. It is presumed their purpose was religious or symbolic, but the exact meanings are largely lost. What does remain is an uncanny sense of presence, sharpened by the abstraction. Collectors of Piravend idols from the Caucasus or Amlash figurines from Iron Age Iran are drawn to the same qualities that captivate visitors to major exhibitions: a tension between the deeply ancient and the strikingly modern.

In recent years, museum exhibitions have helped people see the connections between ancient abstract idols from different parts of the world. By displaying figures from places like the Cyclades, Anatolia and Mesopotamia side by side, curators have shown that many early cultures shared a similar approach to representing the human form. The exhibition Idols: The Power of Images, held at the Fondazione Prada in Venice in 2019, assembled over 80 works from major archaeological museums and private collections; the curators traced a visual lineage of abstraction in human representation from the Neolithic period through to the 3rd millennium B.C.

The ‘Gillet’ Piravend Idol, Iron Age II-III, Circa 1000-650 B.C., North-Western Iran, Bronze, H: 22.8cm, W: 14.3cm, David Aaron Ltd

Sir Leonard Woolley’s excavations at Tell Brak in the 1930s yielded hundreds of the so-called Eye Idols: small, flat stone plaques with exaggerated ocular features. These objects, believed to date from the 4th millennium B.C, have no known counterparts in contemporary traditions. Their stark design – geometric, linear and hypnotic – is one of the earliest attestations of abstraction in human form. In modern contexts, they could be mistaken for works by Paul Klee or Jean Arp.