Journal

Published 5/8/2025

Published 5/6/2025

Published 5/7/2025

Published 5/8/2025

Published 5/16/2025

Published 5/27/2025

Published 6/25/2025

Published 10/21/2025

Published 12/19/2025

Published 2/2/2026

Published 2/5/2026

The Forgotten Princess

Published 18/07/2025

Read time: 4min

As we begin preparations for Frieze Masters 2025, we wanted to take a moment to reflect on one of the stand-out pieces from our stand last year, a rediscovered royal coffin that attracted widespread public and media interest.

Exhibited under the title 'The Forgotten Princess', the coffin was the centrepiece for our Frieze Masters 2024 display. Its presence drew significant attention, not only for its beauty and intricate detailing, but because it is the only known royal Egyptian sarcophagus to have appeared on the art market.

In 2025, the coffin is once again on public display, this time as part of the Making Egypt exhibition at the Young V&A, where visitors can view this exceptional object in person. Its presence not only brings ancient history into focus, but also underlines the value of sustained research, conservation, and responsible curation in the rediscovery of lost narratives.

The Forgotton Princess on display at Frieze Masters, 2024. Photo credit David Owens / co The Art Newspaper

The Forgotten Princess: Early Egyptologists

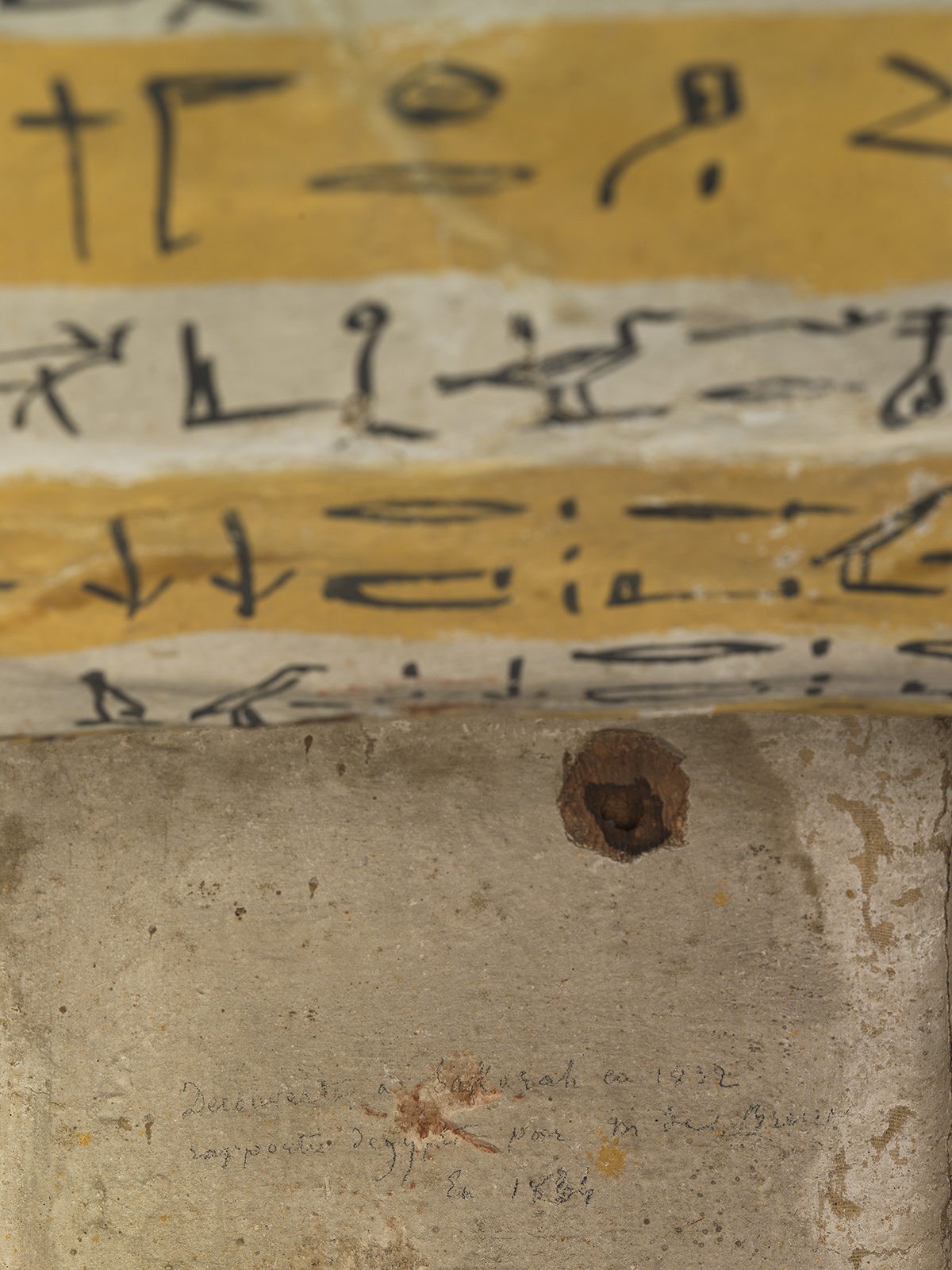

In 2014, a handwritten note was found on the inner base of the coffin, dating back to the early nineteenth-century:

‘Decouverte à Sakara en 1832 / rapportée d’egypte par M J de Breuv[ery] / En 1834’ (‘Discovered in Saqqara in 1832, removed from Egypt by M. J de Breuvery in 1834’)

The handwritten note can be seen on the inside of the base of the coffin.

The ‘M J Breuv[ery]’ in the note is Monsieur Jules Xavier Saguez de Breuvery (1805-1876), a French archaeologist who travelled the Near East, Egypt and Sudan with Édouard Pierre Marie de Cadalvène, between 1829 and 1832. De Breuvery and de Cadalvène published an account of their journey in four volumes, including their social and political commentary on the Ottoman Empire.

In 1829, de Breuvery and de Cadalvène began their journey through Egypt at Alexandria. They spent some time in the city, visiting sites such as Pompey’s Pillar and Cleopatra’s Needles. From here, they set out to Rosetta and Fuwwah, before continuing on to Damietta, where they began their journey down the Nile. Whilst staying in Cairo, the pair toured the pyramids of Giza, Heliopolis, and other notable regions from antiquity. They continued on to Faiyum and to the famous tombs at Beni Hasan, then down towards Abydos, Qurna, where they travelled to the temple at Denderra, before arriving at Thebes:

"Before us lay the immense plain which the ancient metropolis of Egypt covered with its countless buildings. Here and there rose on both banks of the Nile these gigantic ruins before which our republican phalanxes clapped their hands or presented arms, by a spontaneous movement, as if these ruins communicated an involuntary enthusiasm, as if they had a language intelligible to all." (translated) J. de Breuvery and Ed. de Cadalvène, L’Égypte et La Nubie (Paris, 1841), pp. 310-11

They explored much of the region around Thebes, visiting the temple at Karnak, the Ramesseum, the Valley of Kings, Medinet Habu, El-Assassif, and the city of Luxor. They sailed down the Nile past the temples of Esna, Edfu, and Kom Ombo, and through Aswan and Elephantine into what is now Sudan. Their tour then passed through Khartoum, Gebel Adda, Wadi Halfa, and Dongola, to Kordofan. From Kordofan they returned northwards, back to Saqqara. De Breuvery and de Cadalvène’s comprehensive itinerary reveals their keen interest in Egypt and its ancient history, and they even took care to describe the condition of the antiquities they saw on their route.

De Breuvery made several purchases of antiquities during their journey, several of which were inscribed with similar handwritten notes recording the dates he acquired them. Among the objects he brought back to his home at Saint-Germain-en-Laye in France are a caryatide statue from Halicarnassus (Musée du Louvre, Paris, MNC 1382) and the coffin of Princess Sopdet-em-haawt.

De Breuvery and de Cadalvène met many contemporary Egyptologists, archaeologists, and other travellers during their travels. For instance, they met famous explorer and early Egyptologist Robert Hay (1799-1863) at Beni Hasan.

"Mr. Hay, a wealthy English traveller and enthusiastic admirer of Egyptian architecture, was at Beny-Hassan when we arrived, busy carefully drawing the hieroglyphic paintings which decorate the speos of the mountain." (translated) De Breuvery and de Cadalvène, L’Égypte et La Nubie, p. 431.

Hay transcribed the paintings on the Speos Artemidos into one of his meticulous notebooks, where he also recorded a portion of the inscriptions on the coffin of Princess Sopdet-em-haawt. Hay recorded the coffin between 1829 and 1834, when he was living in the village of Gournah in the Theban area. Hay’s drawings, paintings, plans, notebooks and diaries are now in the collection of the British Library, including this notebook (Add.MSS.29827, fol. 83 verso).

Modern Rediscovery

In December 2013, the coffin was sold at Sotheby’s, New York. At this time, the coffin had remained closed, and the details of the internal hieroglyphics and the pencil note remained undiscovered. Still, the coffin had already sparked the interest of several scholars.

In 2009, when the coffin’s whereabouts were not public knowledge and using only the transcribed inscription in Hay’s notebook, Raphaële Meffre traced the lineage of Princess Sopdet-em-haawt in her article ‘Une Princesse Héracléopolitaine de l’Époque Libyenne: Sopdet(em)haaout’ (Revue d’Égyptologie, 60 (2009), pp. 215-221). As a descendant of two Libyan kings, the princess’s coffin can be dated to either the very end of the 25th Dynasty or, more likely, the beginning of the 26th. Sopdet-em-haawt was married to a member of one of the most important Theban families; her husband was involved in the cults of Amun and of Montu, whose priests were among the most influential people in Thebes from the end of the Libyan Period to the 26th Dynasty.

However, it was not until 2014 when the coffin was painstakingly cleaned, conserved, and opened by conservators that much of the internal hieroglyphs became visible, and the incredibly well-preserved striped interior inscriptions were uncovered. The new discoveries prompted Meffre to study the coffin in greater detail. In 2015, she published a complete, 54-page translation of the coffin’s internal and external inscriptions (‘Le cercueil intérieur de la princesse Sopdet-em-hââout et la famille des rois Roudamon et Peftjaouâuybastet’, Monuments et mémoires de la Fondation Eugène Piot, 94 (2015), pp. 7-59).

The Princess Sopdet-em-haawt lived during a pivotal regime shift between the end of the Third Intermediate Period and the establishment of the Late Period. Her coffin is highly important in expanding our knowledge of workshops in the Theban area at the beginning of the Late Period. This, alongside the extremely well-preserved decoration, given new life through extensive conservation, and the rediscovered nineteenth-century provenance, makes the coffin of Sopdet-em-haawt a truly unique example of an ancient Egyptian coffin on the market today.

Making Egypt - Exhibition at Young V&A

The coffin of Princess Sopdet-em-haawt is on view as part of Making Egypt, the major new exhibition at the Young V&A, running until 2 November 2025. The exhibition offers a rare chance to examine the coffin's beautifully preserved decoration up close, including the striking internal yellow and white stripes, and reflects on how ancient Egypt has influenced art, design and popular culture today.

The inner sarcophagus of Princess Sopdet-em-haawt on view as part of Making Egypt, Young V&A, 2025. Courtesy Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Photo: David Parry