Journal

The Artist as Collector: Jacob Epstein

Published 5/8/2025

The Attraction of Abstract Idols

Published 5/7/2025

Corsican Bronzes: One-Way Track to the Past

Published 5/8/2025

Amlash Pottery

Published 06/05/2025

Read time: 5min

In Gilan Province in northwestern Iran, just south of the Caspian Sea, is a series of rich, fertile valleys, populated by olive and fruit trees, rice, wheat and barley plants. The valleys of this region hold many archaeological mounds, the remains of long-ago civilisations, from which a wealth of extraordinary objects of great historic and aesthetic interest have been unearthed. The Iron Age ceramics found around the modern town of Amlash exhibit a unique and easily recognisable style, and provide important archaeological evidence of an otherwise unrecorded civilisation.

Ezat Negahban with finds from Marlik Tepe, The Encyclopædia Iranica

It quickly became clear that these archaeological remains provided evidence of a long-forgotten civilisation. In Negahban’s words, ‘we began to realise that we had discovered the burial mound of a culture that had completely vanished from human memory. The masterpieces of art discovered in these roughly constructed tomb chambers seemed to indicate that this must have been the burial ground of the royal families of this forgotten kingdom’. The objects Negahban discovered at Marlik were of such great variety that he said that if he hadn’t seen them emerge from the same site with his own eyes, he would not have believed it. The case has been made that some of the metalware and jewellery from these digs originated in earlier periods, or were goods traded from other cultures. It is, therefore, predominantly the ceramic vessels and statuettes which are deemed truly representative of Amlash culture.

Amlash Idol, 1st Millennium B.C., Amlash, Central Asia, Terracotta, H: 45cm, David Aaron Ltd

The ceramic vessels and statuettes of both humans and animals from this region are by far the most important source we have on the Amlash culture of Iron-Age Iran. The many animal figures usually represent the region’s native fauna, such as rams, horses, stags, boars, oxen, and ibex. Human representations are also common and generally found at burial sites, suggesting that they may represent specific individuals or deities. Much of what has survived seems to have held spiritual or ritual functions, such as these votive idols, and libation vessels.

Since their appearance on the antiquities market in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Amlash ceramics have been of great interest to modern collectors and museums throughout the world. Their abstracted but immediately recognisable silhouettes appealed greatly to the early twentieth-century avant-garde. Artists were drawn to what they saw as a skilful reduction of figures to pure form. For instance, Pablo Picasso, who had been fascinated with the bull and bull-fighting from an early age, was known to have owned several bull-shaped libation vessels of Amlash type. A clear line of influence can be seen from these to Picasso’s ceramic works, such as his Standing Bull (1947).

In 1961, a large travelling exhibition of Iranian Art opened in Paris. ‘7000 Years of Iranian Art’ featured many fine examples of Amlash ceramics and metalwork, and brought them to the notice of the general public. Charles K. Wilkinson, then-Curator Emeritus of Near Eastern Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, wrote that, ‘Many of these objects of unglazed earthenware, grotesque in form and visually arresting, appealed strongly to people who ask of art something more than mere prettiness and mirror reflections of creatures and men of this world’. Although this was Amlash art’s Western debut, many of the pieces in the exhibition were loaned from private collections, where they had already been snapped up by keen connoisseurs.

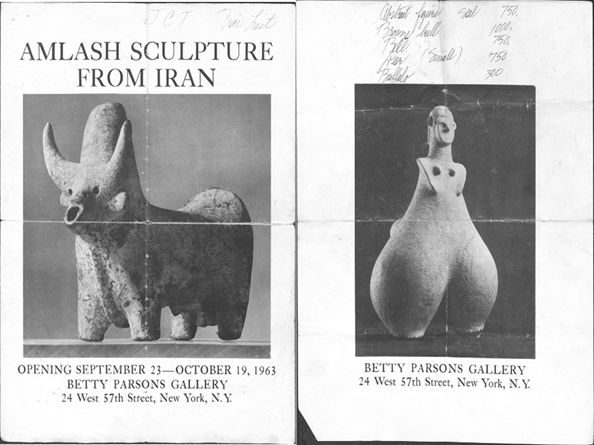

One of the most arresting anthropomorphic Amlash figures to ever appear on the market is this large and intact steatopygous figure, 31 cm high, with an unmistakably female form, pictured above. Full hips swell below pronounced buttocks, tapering above to very narrow shoulders and thinning to two circular feet at the base. This produces a striking silhouette. The features are abstracted, with stylised limbs positioned below the two clearly modelled breasts. Five incised lines decorate the neck, probably representing jewellery, and small round ears protrude on either side of the head. The pierced ears may have originally been adorned with bronze or gold earrings, as other Marlik figures were.

This idol was one of the centrepieces of an exhibition of Amlash sculpture at Betty Parsons Gallery, New York, in 1963. Betty Parsons (1900-1982) was an American artist, art dealer, and collector known for her early promotion of Abstract Expressionism. Her New York gallery featured works by Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Ad Reinhardt, Clyfford Still, and Barnett Newman, long before they achieved mainstream popularity. Invitees of her 1963 exhibition included cubist sculptor Jacques Lipchitz and Joseph Epstein, editor of The American Scholar. In the exhibition catalogue, Barnett Newman wrote that Amlash art is ‘unlike any sculpture known’ and that, ‘It is becoming more and more apparent that to understand Modern art, one must have an appreciation of the primitive arts, for just as modern art stands as an island of revolt in the stream of western European aesthetics, the many primitive art traditions stand apart as authentic aesthetic accomplishments’.

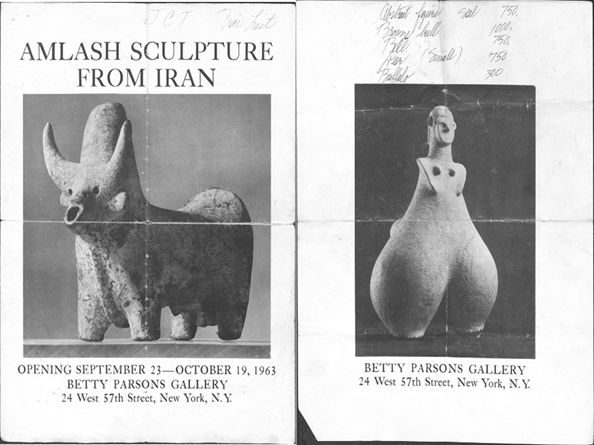

Poster advertising the exhibition curated by Betty Parsons, 1963

In 1964, the Jerrold Morris International Gallery, Toronto, possibly inspired by the positive press coverage of Parson’s exhibition, held his own exhibition of Amlash art. Many of the works featured in both exhibitions were lent by Samuel Dubiner and Barry Kernerman of Galerie Israel, Tel Aviv. Dubiner remains to this day one of the most preeminent collectors of Bronze Age Iranian artworks. In the 1970s, he produced, wrote, and narrated a series of short films about Amlash art entitled The Amlash Connection, featuring many pieces from his private collection.

Amlash ceramics continue to have a strong appeal today. Several examples featured in the 2021 ‘Epic Iran’ exhibition at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, including a humped bull from the Ashmolean Museum and a steatopygic female figurine from the Sarikhani Collection.

Discovering Iron Age Amlash

Finds from this region have passed through the small market town of Amlash on their way into the antiquities markets of Iran, Europe and the US since the 1930s, prompting official excavations licensed by the Iranian government. In 1960, a team of Japanese archaeologists from Tokyo University led by Namio Egami excavated tomb sites in Deylaman. Here they found bronze and iron weaponry, horse equipage, mirrors, gold and silver jewellery, and bronze and ceramic figures of animals. Similar objects were found during the 1961 excavation of the Marlik tomb site on the Sefid Rud by renowned Iranian archaeologist Ezat Negahban. The fifty-three tomb chambers of Marlik Tepe, dated between 1100 and 800 B.C., contained many gold and silver vessels, weapons, jewellery, and grey- and red-ware ceramic vessels. Other ceramic finds from the nearby site of Kalaruz and the more distant Kalar Dasht share many characteristics with those found at Marlik.

Ezat Negahban with finds from Marlik Tepe, The Encyclopædia Iranica

It quickly became clear that these archaeological remains provided evidence of a long-forgotten civilisation. In Negahban’s words, ‘we began to realise that we had discovered the burial mound of a culture that had completely vanished from human memory. The masterpieces of art discovered in these roughly constructed tomb chambers seemed to indicate that this must have been the burial ground of the royal families of this forgotten kingdom’. The objects Negahban discovered at Marlik were of such great variety that he said that if he hadn’t seen them emerge from the same site with his own eyes, he would not have believed it. The case has been made that some of the metalware and jewellery from these digs originated in earlier periods, or were goods traded from other cultures. It is, therefore, predominantly the ceramic vessels and statuettes which are deemed truly representative of Amlash culture.

Amlash Idol, 1st Millennium B.C., Amlash, Central Asia, Terracotta, H: 45cm, David Aaron Ltd

Modern Fascination with the Ancient

Since their appearance on the antiquities market in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Amlash ceramics have been of great interest to modern collectors and museums throughout the world. Their abstracted but immediately recognisable silhouettes appealed greatly to the early twentieth-century avant-garde. Artists were drawn to what they saw as a skilful reduction of figures to pure form. For instance, Pablo Picasso, who had been fascinated with the bull and bull-fighting from an early age, was known to have owned several bull-shaped libation vessels of Amlash type. A clear line of influence can be seen from these to Picasso’s ceramic works, such as his Standing Bull (1947).

In 1961, a large travelling exhibition of Iranian Art opened in Paris. ‘7000 Years of Iranian Art’ featured many fine examples of Amlash ceramics and metalwork, and brought them to the notice of the general public. Charles K. Wilkinson, then-Curator Emeritus of Near Eastern Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, wrote that, ‘Many of these objects of unglazed earthenware, grotesque in form and visually arresting, appealed strongly to people who ask of art something more than mere prettiness and mirror reflections of creatures and men of this world’. Although this was Amlash art’s Western debut, many of the pieces in the exhibition were loaned from private collections, where they had already been snapped up by keen connoisseurs.

One of the most arresting anthropomorphic Amlash figures to ever appear on the market is this large and intact steatopygous figure, 31 cm high, with an unmistakably female form, pictured above. Full hips swell below pronounced buttocks, tapering above to very narrow shoulders and thinning to two circular feet at the base. This produces a striking silhouette. The features are abstracted, with stylised limbs positioned below the two clearly modelled breasts. Five incised lines decorate the neck, probably representing jewellery, and small round ears protrude on either side of the head. The pierced ears may have originally been adorned with bronze or gold earrings, as other Marlik figures were.

This idol was one of the centrepieces of an exhibition of Amlash sculpture at Betty Parsons Gallery, New York, in 1963. Betty Parsons (1900-1982) was an American artist, art dealer, and collector known for her early promotion of Abstract Expressionism. Her New York gallery featured works by Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, Ad Reinhardt, Clyfford Still, and Barnett Newman, long before they achieved mainstream popularity. Invitees of her 1963 exhibition included cubist sculptor Jacques Lipchitz and Joseph Epstein, editor of The American Scholar. In the exhibition catalogue, Barnett Newman wrote that Amlash art is ‘unlike any sculpture known’ and that, ‘It is becoming more and more apparent that to understand Modern art, one must have an appreciation of the primitive arts, for just as modern art stands as an island of revolt in the stream of western European aesthetics, the many primitive art traditions stand apart as authentic aesthetic accomplishments’.

Poster advertising the exhibition curated by Betty Parsons, 1963

In 1964, the Jerrold Morris International Gallery, Toronto, possibly inspired by the positive press coverage of Parson’s exhibition, held his own exhibition of Amlash art. Many of the works featured in both exhibitions were lent by Samuel Dubiner and Barry Kernerman of Galerie Israel, Tel Aviv. Dubiner remains to this day one of the most preeminent collectors of Bronze Age Iranian artworks. In the 1970s, he produced, wrote, and narrated a series of short films about Amlash art entitled The Amlash Connection, featuring many pieces from his private collection.

Amlash ceramics continue to have a strong appeal today. Several examples featured in the 2021 ‘Epic Iran’ exhibition at the Victoria & Albert Museum, London, including a humped bull from the Ashmolean Museum and a steatopygic female figurine from the Sarikhani Collection.