Journal

Amlash Pottery

Published 5/6/2025

The Attraction of Abstract Idols

Published 5/7/2025

Corsican Bronzes: One-Way Track to the Past

Published 5/8/2025

The Artist as Collector: Jacob Epstein

Published 08/05/2025

Read time: 5min

Sir Jacob Epstein was born on New York’s Lower East Side in 1880, the third son to Polish Jewish immigrant parents. He developed an interest in drawing due to long periods of illness caused by pleurisy in his childhood. He began studying at the Arts Students’ League from the age of thirteen. At first, Epstein made his living by working in a bronze foundry, but he continued to take evening classes in sculpting. His first major commission was to illustrate Hutchins Hapgood’s 1902 book The Spirit of The Ghetto, and he used his earnings from this to move to Paris that same year.

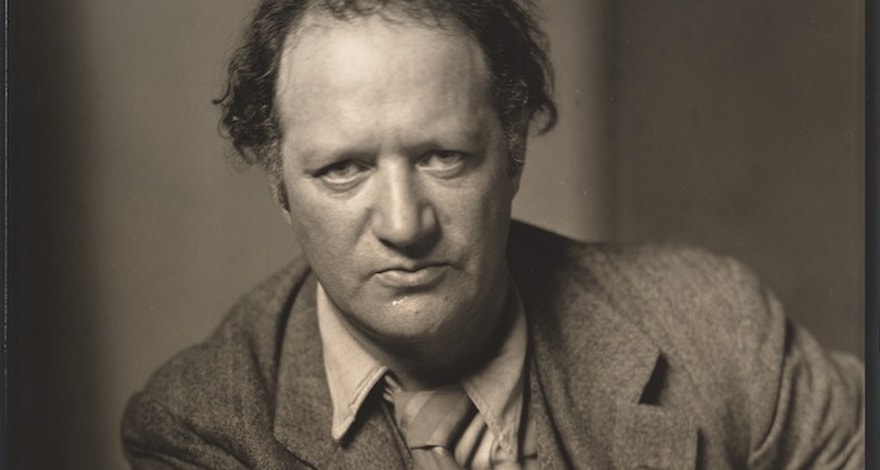

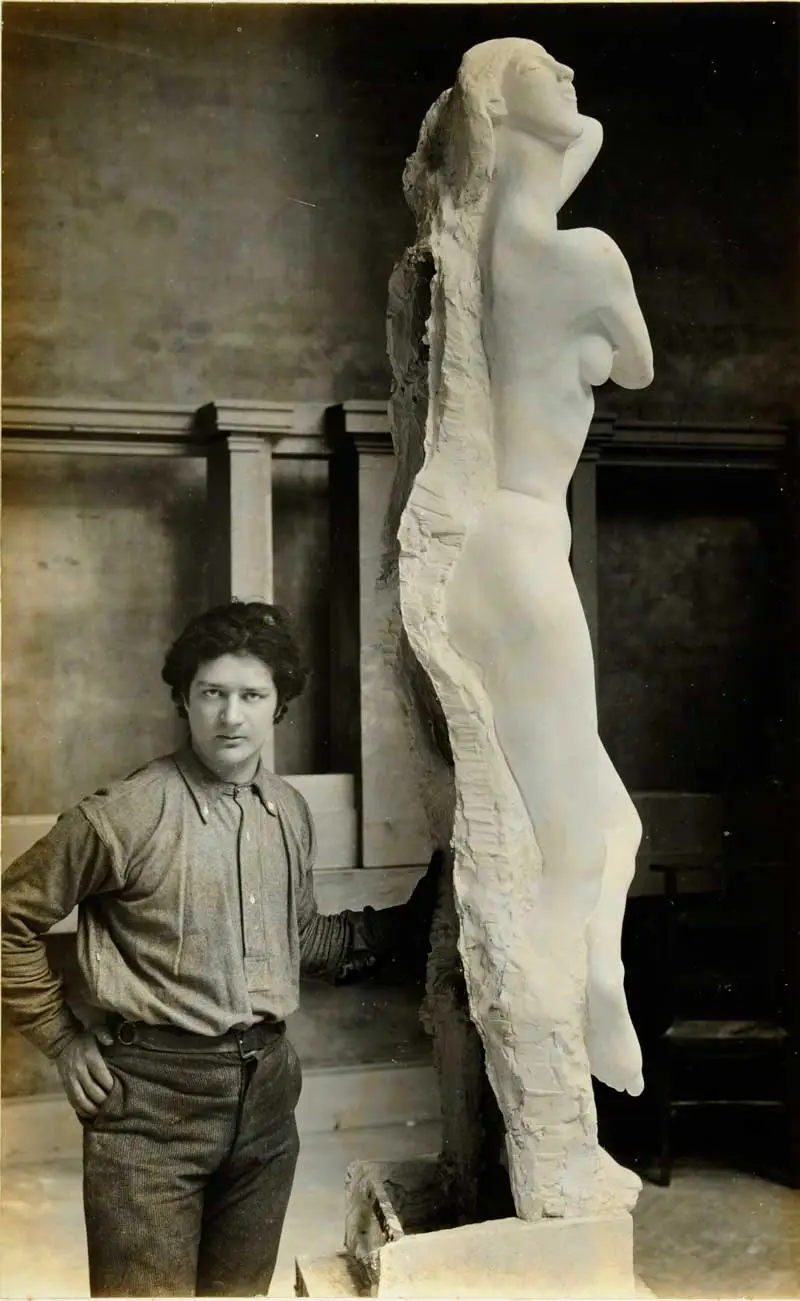

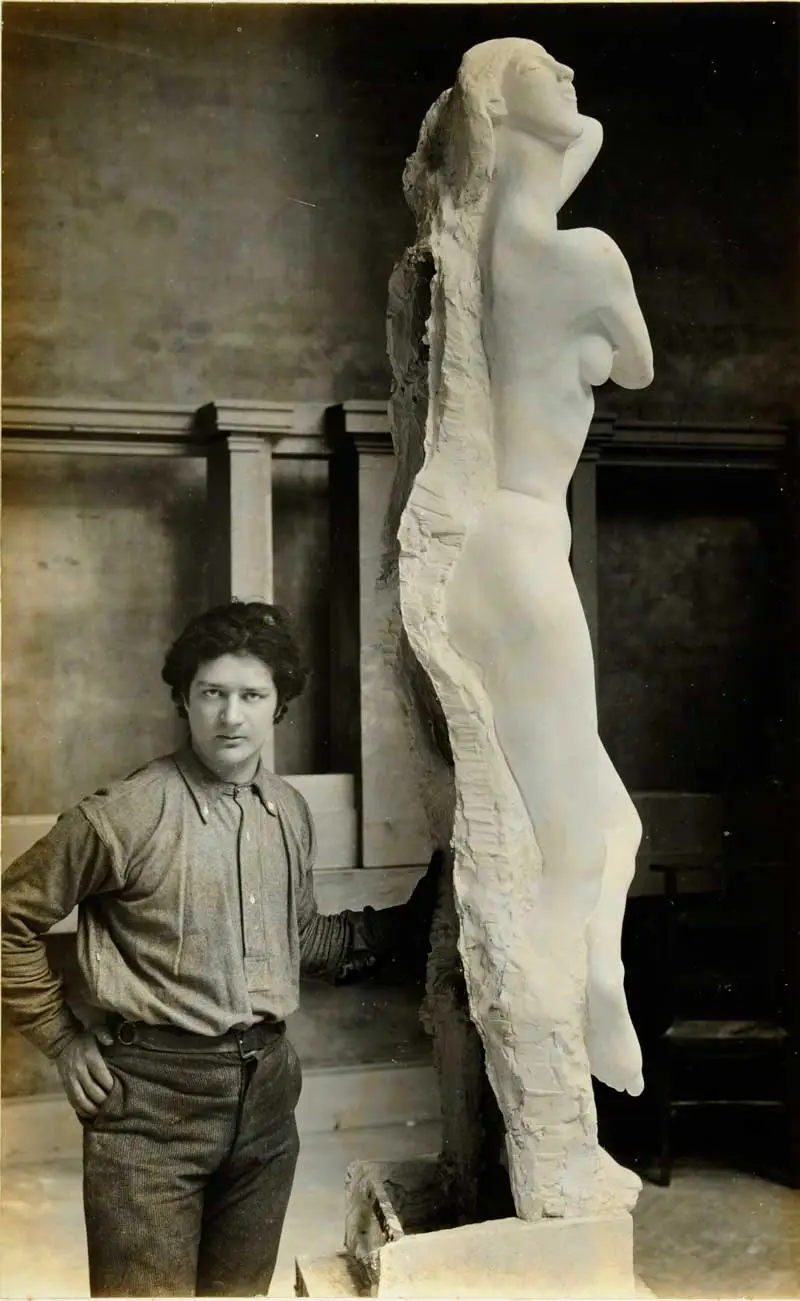

Jacob Epstein at work on one of the statues for the British Medical Association building, The Sketch (8 July 1908)

In Paris, Epstein studied sculpture at the Académie Julian and the École des Beaux-Arts; though his studies ended prematurely at the latter after his studio was destroyed as punishment for his refusal to perform menial tasks for the entrants in the Prix de Rome Concours. He visited the Louvre and saw artworks from outside the Western canon that were less known in Europe at that time, including early Greek work, Cycladic sculpture, the Lady of Elche bust, and the limestone bust of Akhenaten. At the Trocadéro and the Musée Cernusci, he observed what was then known as ‘primitive’ sculpture and Chinese art. In 1905, Epstein moved to London, where he would live for most of the rest of his life – he married Margaret Dunlop in 1906, and took British citizenship in 1911. Epstein spent a great deal of time in the British Museum, studying the Elgin Marbles and other Greek, Egyptian, African, and Polynesian sculptures, and used his observations to develop his own sculptural technique.

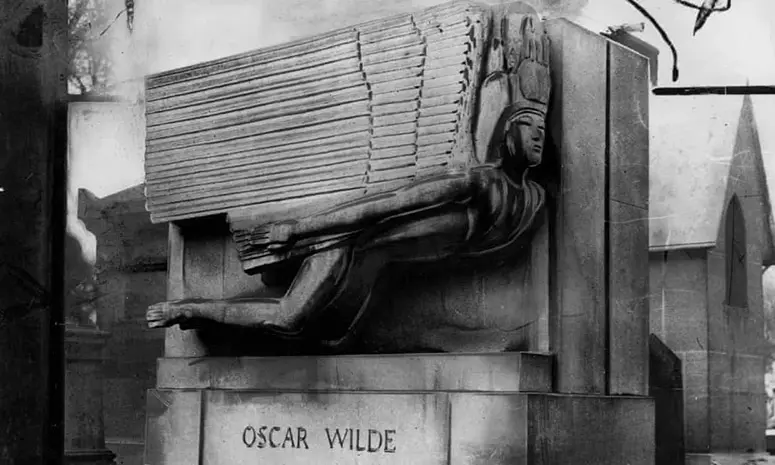

In 1907-8, Epstein was invited by architect Charles Holden to carve eighteen over-life-size figures for the façade of the British Medical Association’s new headquarters in The Strand. For this work, Epstein drew from the ancient and ‘primitive’ works he had studied, and suggested a series of nudes, ‘to express in sculpture the great primal facts of men and women’. According to his 1940 autobiography, Let There Be Sculpture, Epstein was taken completely by surprise at the level of vitriol and controversy sparked by this commission. Though many known figures and artists defended his pieces, public outcry made Epstein a household name and was to follow him throughout his career. For instance, the tomb he carved with Eric Gill for Oscar Wilde in Paris in 1911-12 and his 1915 Rock Drill sculpture prompted similar responses. One critic described Epstein as ‘a sculptor in revolt, who is in deadly conflict with the ideas of current sculpture’. His contemporary Henry Moore praised Epstein for unflinchingly bearing the weight of prejudice and hostility to forge a path for those sculptors who followed him, and expressed great gratitude for Epstein’s courage.

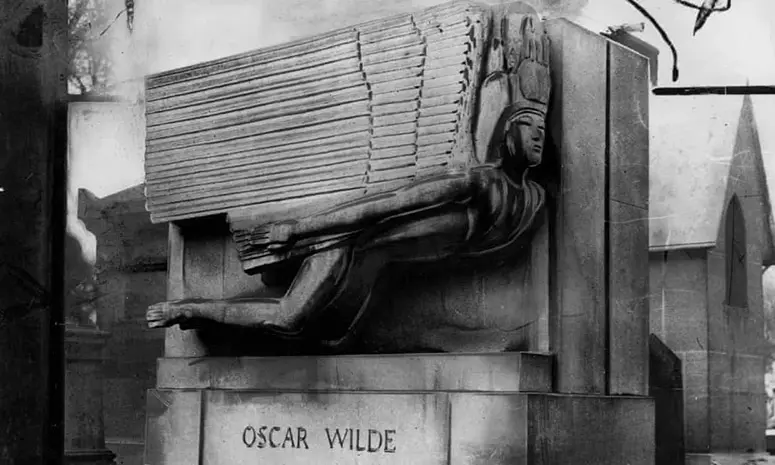

Oscar Wilde's tomb, located in Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris.

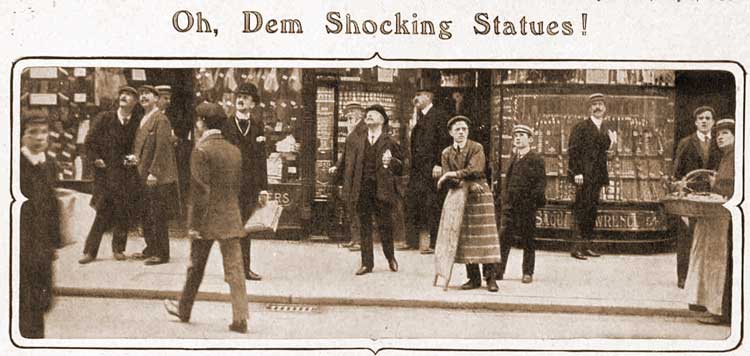

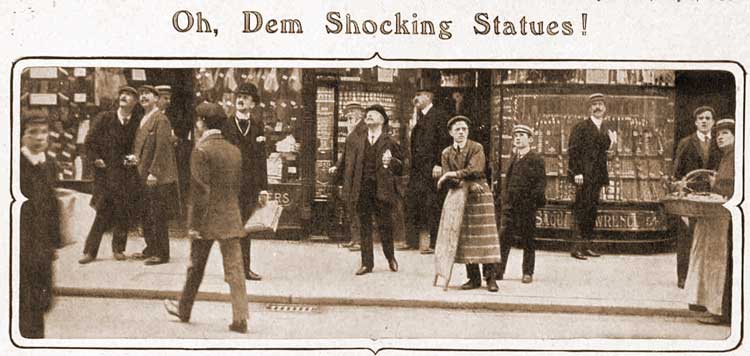

‘Pedestrians on the Strand eagerly gazing up at the building of the British Medical Association, in search of the statues which the papers said were rather shocking and ought to be suppressed.’ From The Bystander (1st July, 1908).

Three nude male figures from the Ages of Man series, former British Medical Association building, now Zimbabwe House, The Strand, London.

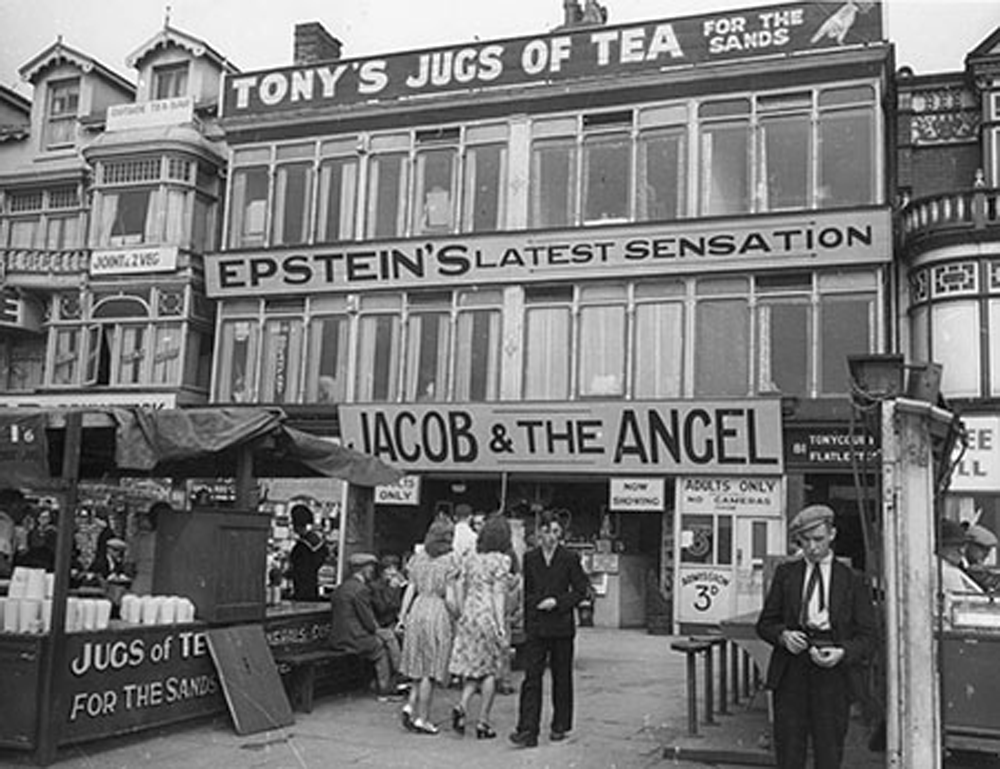

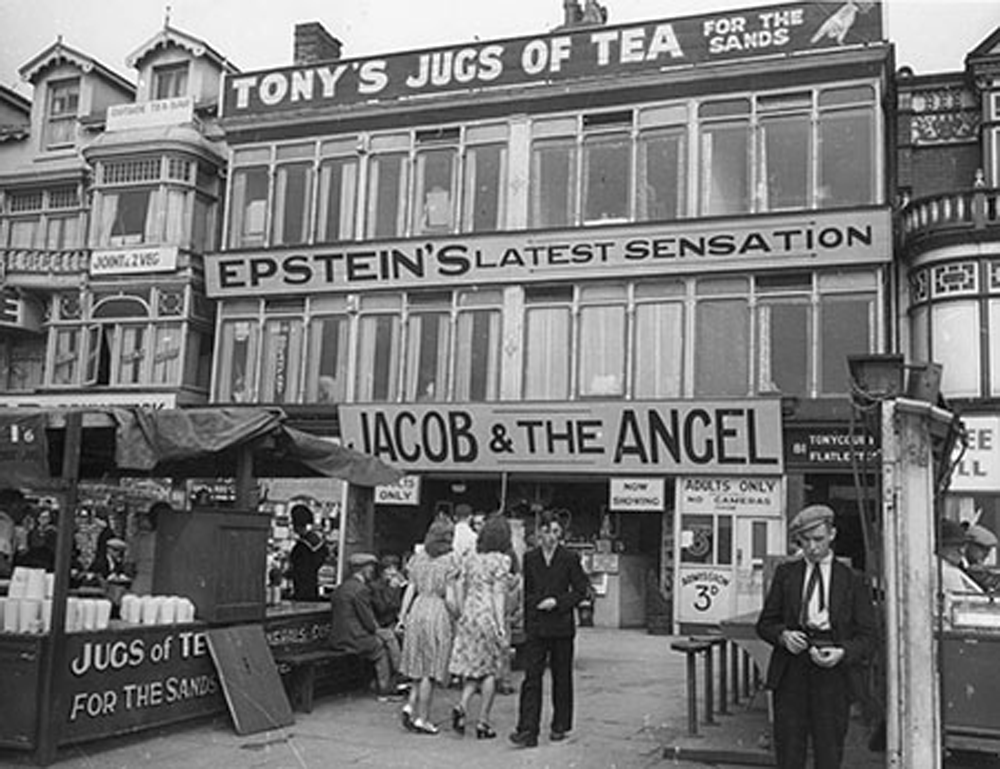

Signs advertising Epstein’s Jacob and the Angel (1940-1) at Louis Tussaud’s Waxworks, Blackpool

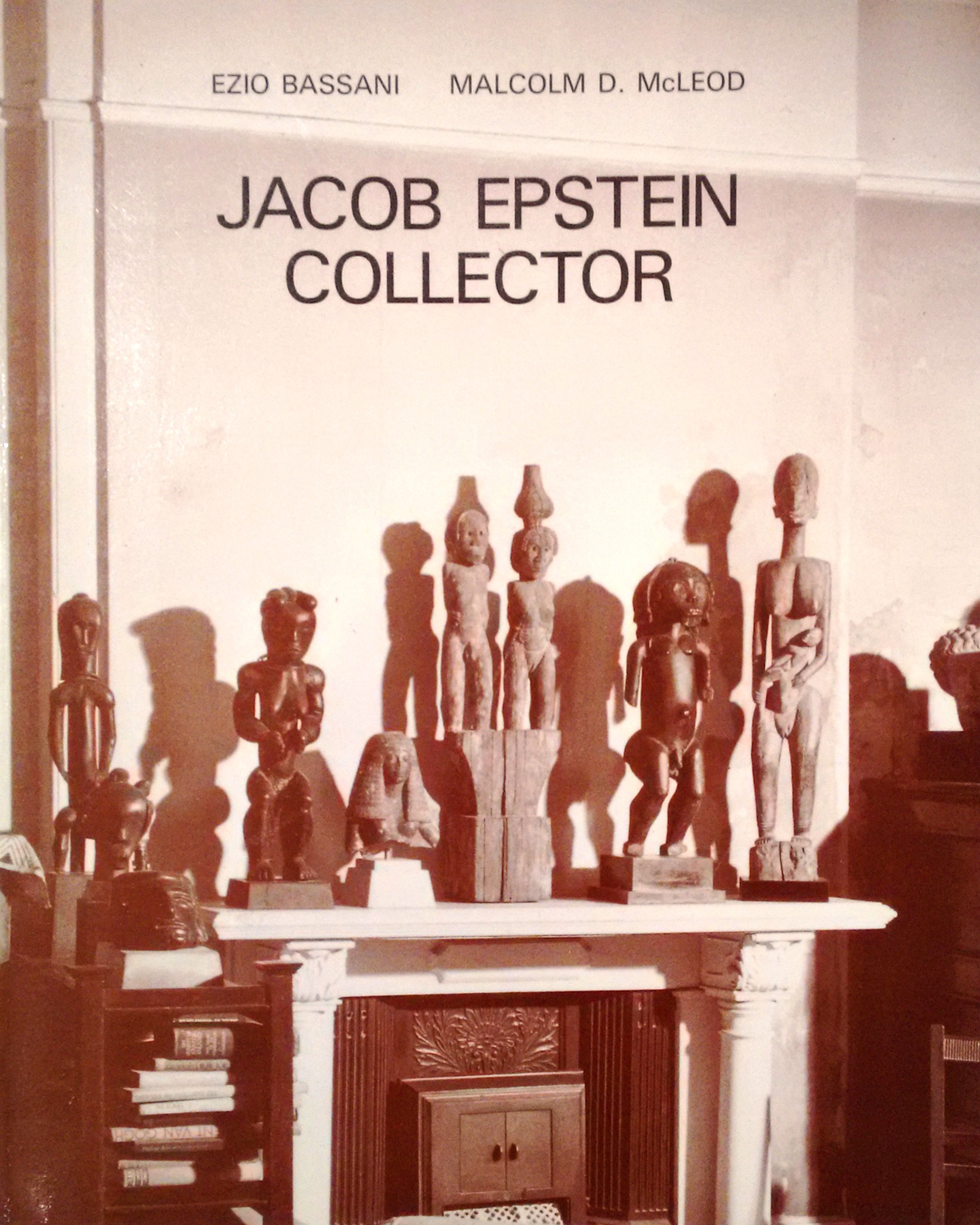

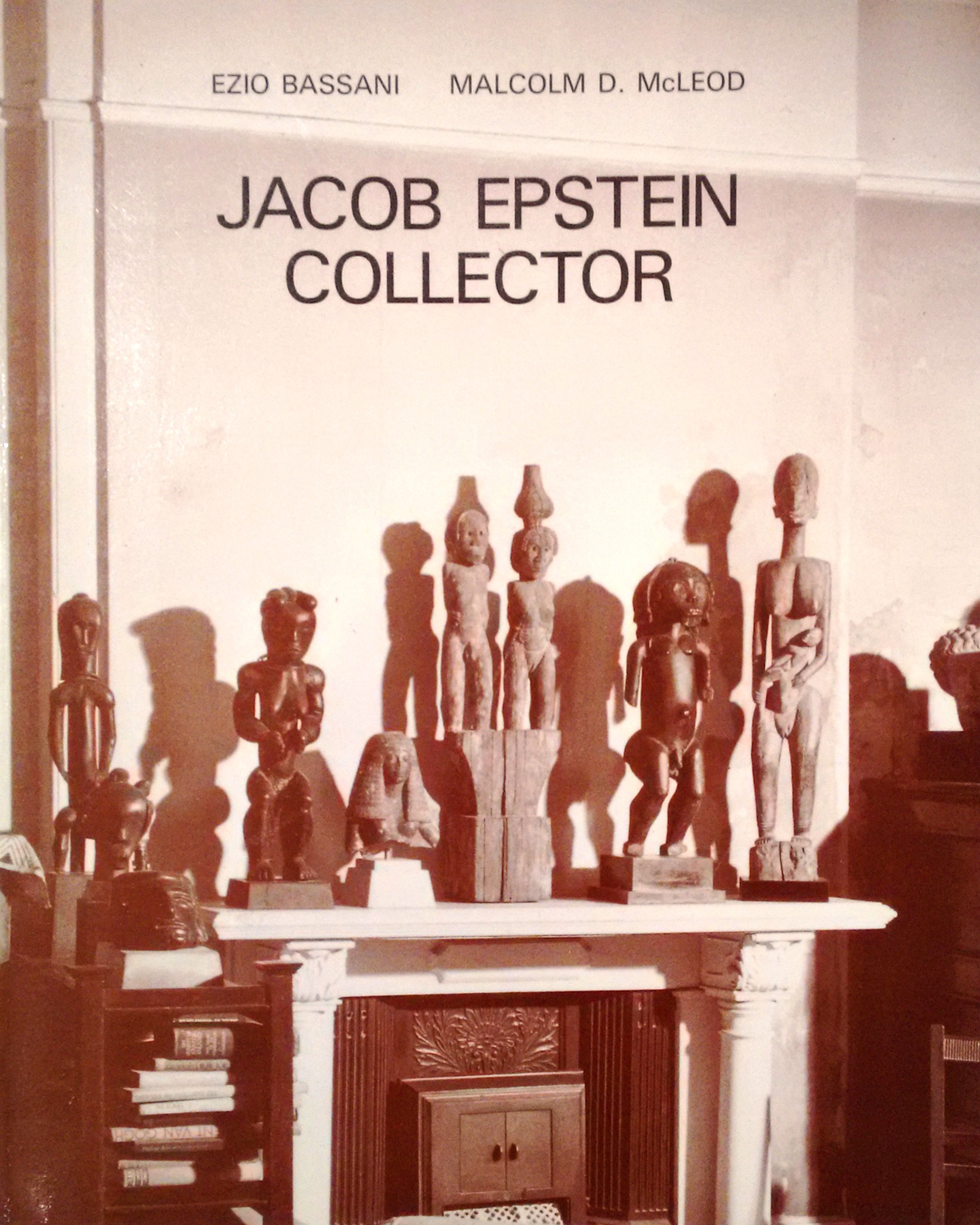

'Jacob Epstein Collector', front cover showing the interior of Epstein's home and some of his collection of African art. Published by Associazione Poro (Milan, Italy, 1989)

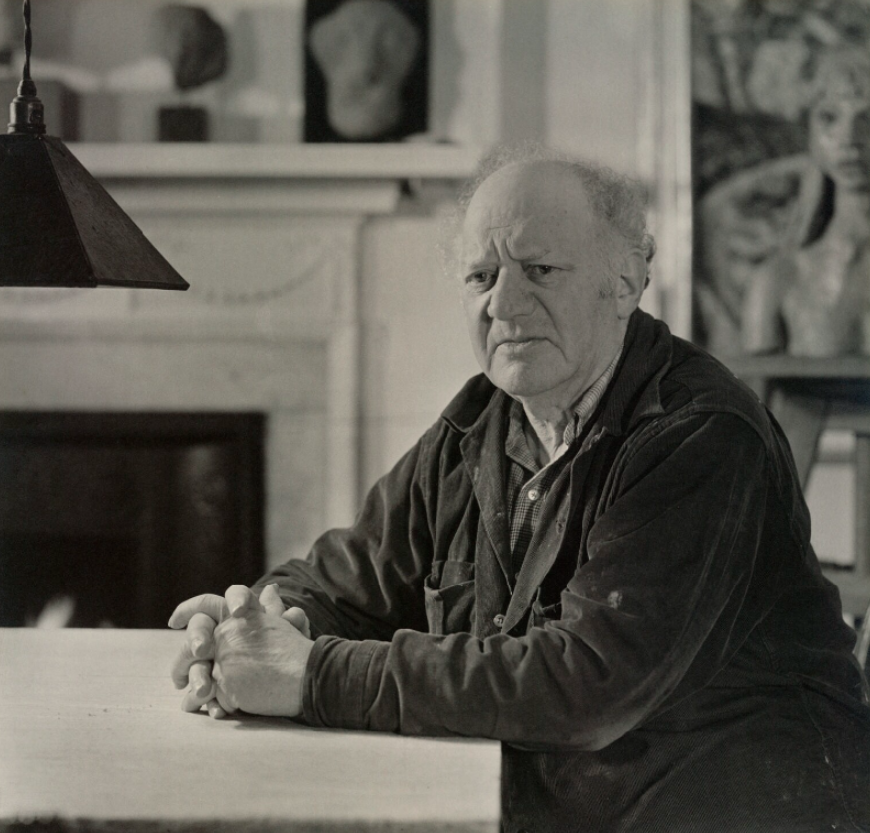

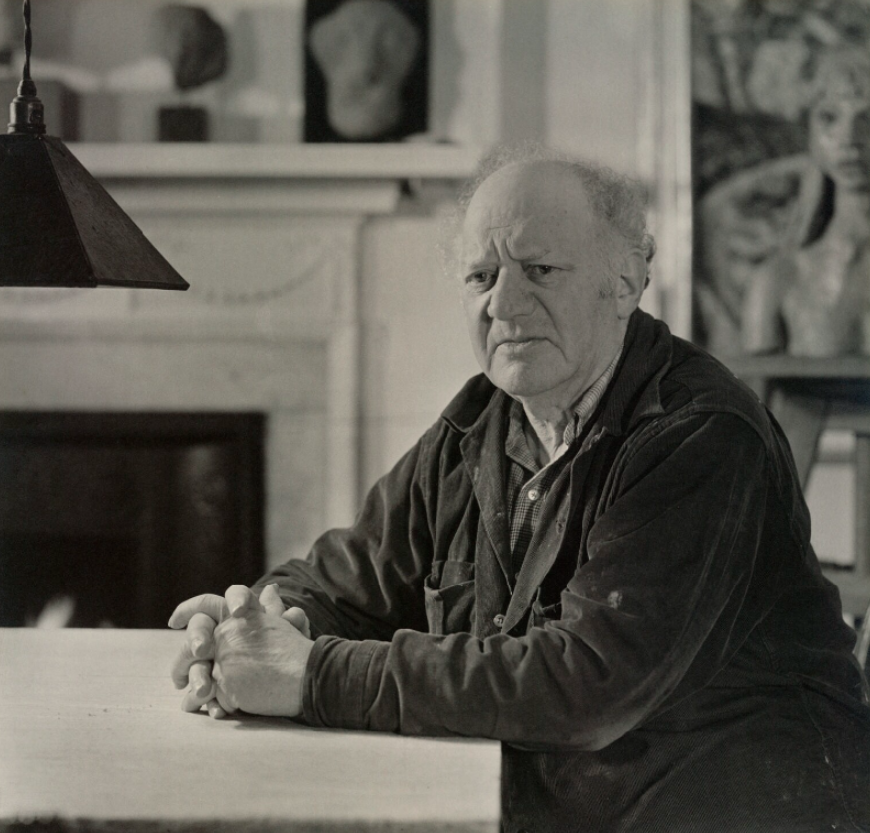

Portrait of Jacob Epstein, Geoffrey Ireland. Ancient Egyptian items from Epstein’s collection can be seen on the mantlepiece behind him. National Portrait Gallery.

Pregnant Cycladic Idol, 2500-2000 B.C., Greece, Marble, H: 14.5 cm, previously in the Private Collection of Sir Jacob Epstein. David Aaron Ltd

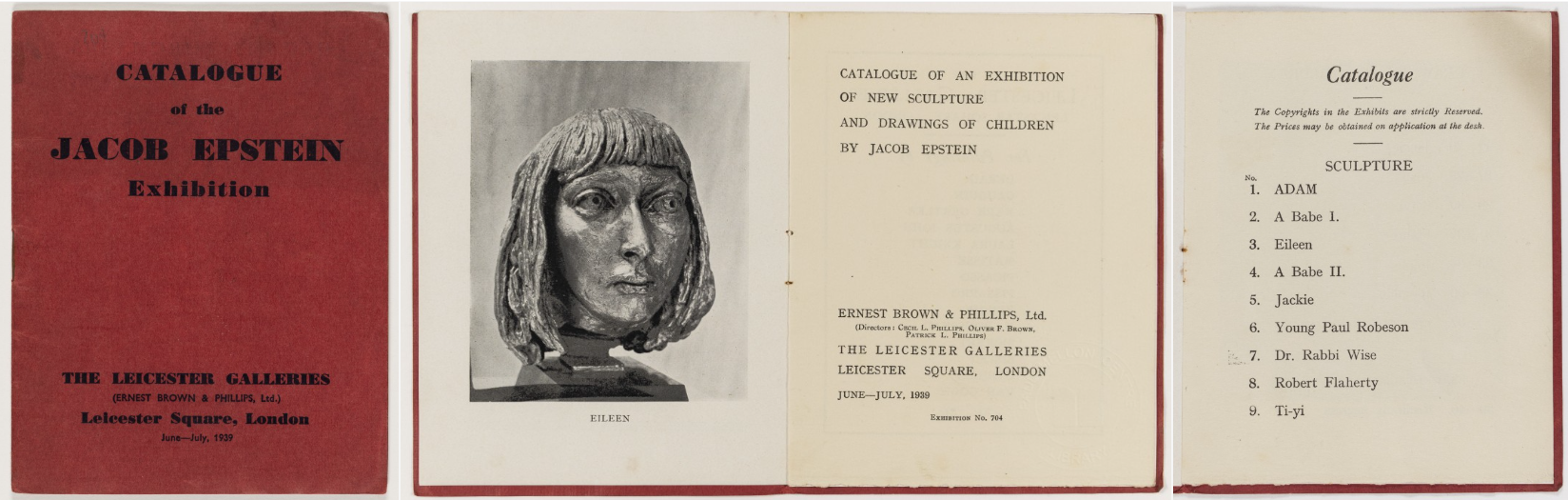

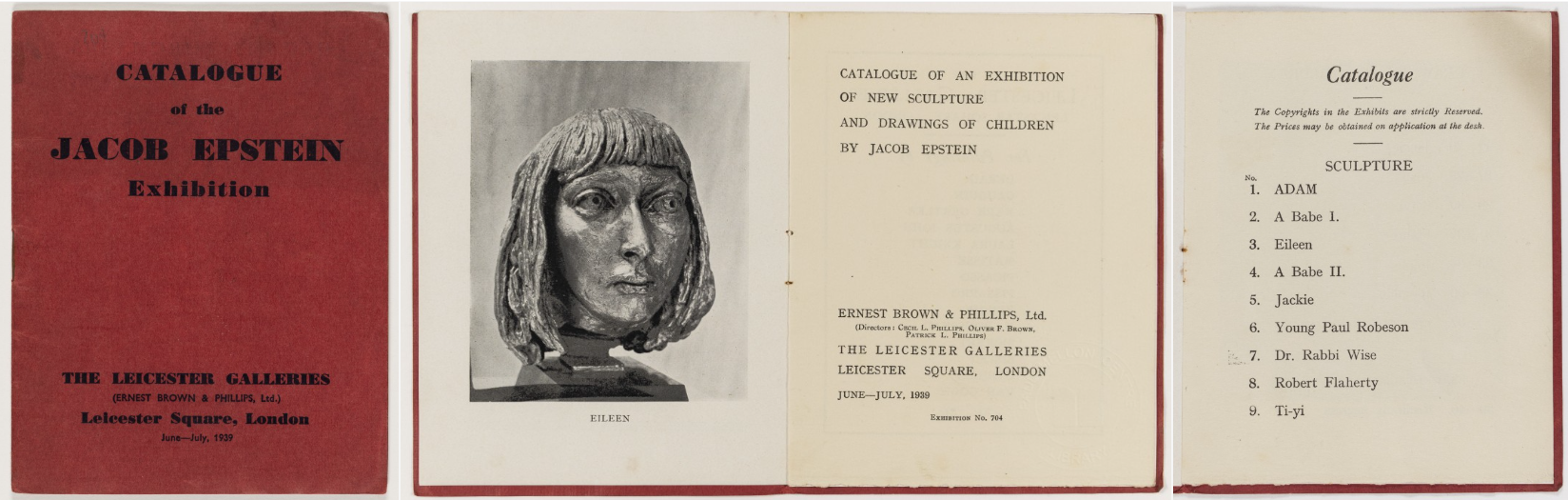

In the 1939 exhibition catalogue, Epstein showcased multiple works, including busts of children and the sculpture of 'ADAM'.

The monumental sculpture of 'ADAM' was later on show in Blackpool. The exhibition received mixed reviews, and a Pathé newsreel shows crowds attending, including a woman fainting.

Cycladic Idol, 2500-2000 B.C., Greece, Marble, H: 21.4 cm, previously in the Private Collection of Sir Jacob Epstein. David Aaron Ltd.

Jacob Epstein at work on one of the statues for the British Medical Association building, The Sketch (8 July 1908)

In Paris, Epstein studied sculpture at the Académie Julian and the École des Beaux-Arts; though his studies ended prematurely at the latter after his studio was destroyed as punishment for his refusal to perform menial tasks for the entrants in the Prix de Rome Concours. He visited the Louvre and saw artworks from outside the Western canon that were less known in Europe at that time, including early Greek work, Cycladic sculpture, the Lady of Elche bust, and the limestone bust of Akhenaten. At the Trocadéro and the Musée Cernusci, he observed what was then known as ‘primitive’ sculpture and Chinese art. In 1905, Epstein moved to London, where he would live for most of the rest of his life – he married Margaret Dunlop in 1906, and took British citizenship in 1911. Epstein spent a great deal of time in the British Museum, studying the Elgin Marbles and other Greek, Egyptian, African, and Polynesian sculptures, and used his observations to develop his own sculptural technique.

In 1907-8, Epstein was invited by architect Charles Holden to carve eighteen over-life-size figures for the façade of the British Medical Association’s new headquarters in The Strand. For this work, Epstein drew from the ancient and ‘primitive’ works he had studied, and suggested a series of nudes, ‘to express in sculpture the great primal facts of men and women’. According to his 1940 autobiography, Let There Be Sculpture, Epstein was taken completely by surprise at the level of vitriol and controversy sparked by this commission. Though many known figures and artists defended his pieces, public outcry made Epstein a household name and was to follow him throughout his career. For instance, the tomb he carved with Eric Gill for Oscar Wilde in Paris in 1911-12 and his 1915 Rock Drill sculpture prompted similar responses. One critic described Epstein as ‘a sculptor in revolt, who is in deadly conflict with the ideas of current sculpture’. His contemporary Henry Moore praised Epstein for unflinchingly bearing the weight of prejudice and hostility to forge a path for those sculptors who followed him, and expressed great gratitude for Epstein’s courage.

Oscar Wilde's tomb, located in Père Lachaise Cemetery, Paris.

‘Pedestrians on the Strand eagerly gazing up at the building of the British Medical Association, in search of the statues which the papers said were rather shocking and ought to be suppressed.’ From The Bystander (1st July, 1908).

Three nude male figures from the Ages of Man series, former British Medical Association building, now Zimbabwe House, The Strand, London.

After the First World War, Epstein received relatively few commissions, although his notoriety continued. Between the 1930s and mid-1950s, some of Epstein’s sculptures were exhibited within the anatomical curiosity section of Louis Tussaud’s waxworks, alongside diseased body parts and conjoined twin babies preserved in jars. Epstein’s bronze portraits were received more favourably; these depicted a range of figures, from his mistress and later wife Kathleen Garman, to Albert Einstein, to ragamuffin children. In the 1950s, Epstein received some important public commissions, including the statue of Jan Smuts in Parliament Square. Epstein was appointed a Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire in the 1954 New Year Honours. In 1958, Epstein was confined to hospital due to illness, but continued to work even up to the day of his death in 1959.

Signs advertising Epstein’s Jacob and the Angel (1940-1) at Louis Tussaud’s Waxworks, Blackpool

'Jacob Epstein Collector', front cover showing the interior of Epstein's home and some of his collection of African art. Published by Associazione Poro (Milan, Italy, 1989)

Sculptural Bust from a Reliquary Ensemble (The Great Bieri), 19th century, Wood and copper alloy, H46.5cm. Previously in the private collection of Jacob Epstein, now with the Metropolitan Museum, NY, USA.

Epstein dated the start of his collection of African sculpture to around 1905 – the same time that Picasso, Vlaminck, and Matisse began to express their interest in such pieces, putting him at the forefront of Western interest in ‘primitive’ art. The dealer Paul Guillaume, writing in 1917, described Epstein as ‘le promoteur’ of African art in England. In 1924, Henry Moore visited Epstein’s house in Hyde Park Gate, and remarked that his bedroom ‘was so overflowing with negro sculpture etc., that I wondered how he got into bed without knocking something over’. By the time Arnold Haskell interviewed the artist in 1931, Epstein had around 200 statues, masks, and ivories. Each week during his conversations with Haskell, Epstein would rearrange the room with different items from his collection. By Haskell’s account ‘This is certainly the finest private collection in England, and one of the finest in the world. Each piece is the work of some remarkable unknown artist, and there are few, very few, ‘mistakes’ amongst them … There is none of the deadness of the museum here, and the works have not lost their individuality.’[1] Epstein himself took great pride in his collection, asserting that his possessions were superior to or more authentic than others’.

Portrait of Jacob Epstein, Geoffrey Ireland. Ancient Egyptian items from Epstein’s collection can be seen on the mantlepiece behind him. National Portrait Gallery.

Pregnant Cycladic Idol, 2500-2000 B.C., Greece, Marble, H: 14.5 cm, previously in the Private Collection of Sir Jacob Epstein. David Aaron Ltd

Epstein collected with great voracity, often acquiring pieces before he had money in hand to pay for them (several of these debts were only paid off after his death). He eventually had over 1,000 pieces in his collection at Hyde Park Gate. Although Epstein’s name rarely appears in the price lists of auction houses like Sotheby’s, he is known to have purchased items through a range of avenues, including the London dealer John Hewett, and Galerie Apollinaire. He was persistent in chasing what he felt were quality pieces – for instance, he first enquired about the ‘Brummer Head’ while it was still in the possession of Joseph Brummer well before 1913, and eventually purchased it in 1935 when he discovered it in a dealer’s basement. Epstein also advised other collectors of African art, including Helena Rubinstein, whom he met in 1909.

Epstein professed that he was not interested in works for their ethnographical import, but for their artistic and formal qualities. He claimed he had two collections: one with the best works of art he could find on the market, and one he made for himself as an artist, of lesser works that gave him new ideas around formal issues. Epstein praised the ‘restraint in craftsmanship, delicacy and sensitiveness, [and] regard for the material’ he saw in ‘primitive’ sculpture.[1] Epstein’s own work, such as Female Figure in Flenite (1913) and Venus (1917), incorporated the simple yet evocative forms that he admired in non-Western figures.

In the 1939 exhibition catalogue, Epstein showcased multiple works, including busts of children and the sculpture of 'ADAM'.

The monumental sculpture of 'ADAM' was later on show in Blackpool. The exhibition received mixed reviews, and a Pathé newsreel shows crowds attending, including a woman fainting.

After Epstein’s death in 1959, the Arts Council held a memorial exhibition featuring most of the works from his collection. In 1963, Carlo Monzino bought the major part of the collection, in what he described as ‘the culminating moment for me’. Since then, works from Epstein’s collection have gone on to sell for record-breaking prices and are found in museums around the world. The British Museum has twelve objects from his collection, all purchased in the sale at Christie’s, 15 December 1961, while the Metropolitan Museum has nine, and others are with The Dapper Foundation, Paris.

Cycladic Idol, 2500-2000 B.C., Greece, Marble, H: 21.4 cm, previously in the Private Collection of Sir Jacob Epstein. David Aaron Ltd.